Empty homes are back in the news. The Prime Minister said we can use them to house immigrants. Is he right? Do we have an empty homes problem in the UK? If so, what should we do about it? Can we better use empty homes to house those on the waiting list or immigrants or to meet our housing shortfall?

First off, the data on the subject is pretty good. The census does a superb snapshot every decade and the government uses council tax receipts to estimate numbers more frequently. There is a bit of disagreement on precise numbers between the government and some campaign groups but we basically know the size of the prize and of the challenge.

On the face of it, empty homes are an opportunity. In 2021 at the last census there were 1.5 million empty homes in England. That is 6 per cent of the total housing stock of about 24 million homes in England. Set against over 300,000 people on housing waiting list or an annual new homes requirement of 300,000 to hit the Government’s 1.5 million homes target, this seems like big potatoes.

Have we just discovered a Get out of Jail Free card?

Sadly not. When you dig a little deeper the opportunity largely, though not entirely, slips between your fingers.

The key point is this: in a country with a population of 57 million and about 24 million homes it is not that surprising that there are lots of empty homes on any given day. People die. People get divorced. People move house. People move around the country. Over 200,000 of those empty homes are awaiting probate or belong to recently deceased people. Over 200,000 have been empty for less than six months. Many, though not all, of those will shortly be back in use. Other empty homes are second homes, about 150,000 according to official statistics. This can be a problem in localised tourist hotspots particularly in the south-west and parts of Wales. (The Venice problem) But those second homes also provide local income and tourist pounds.

That leaves us with a round 260,000 long-term empty homes which have been empty for more than six months. These are homes where either the owner does not care or believes he can wait for other opportunities, or which are in bad and declining condition and where the cost of repair is greater than the available income or sales value. This is the opportunity in principle and in practice. 260,000 is much smaller than 1.5 million but it is not trivial if some of them can come back into use.

It is a number that has been trending upwards over the last few years, up from around 200,000 in 2016 though that low was after systemic long-term decline. There were 318,000 empty homes back in 2004. Not surprisingly, we have far fewer empty homes than most other countries with less tight housing markets. Our proportion of just under one percent compares to over 2 per cent in Germany nearly three percent in Greece nearly four per cent in France and up to seven or eight per cent in Portugal Spain and Ireland. Comparatively, we have very few empty homes.

This is not surprising partly because our supply of housing has been so sluggish over recent decades. We are anything up to six and a half million homes short if you compare home to household ratios or comparative build rates in different countries. It is also because for 20 years government have been trying to do something about empty homes with a mixture of carrots and sticks.

Once upon a time, empty homes paid no or less council tax. No longer. That situation was reversed as long ago as 2013 and successive policy tightening now means that once a home has been empty for over a year, high council tax premiums can be applied if councils wish. Various governments have also encouraged local councils to put empty homes back into use with financial incentives. There is also something called an empty dwelling management order (an EMDO) which can be used to bring an empty home back into use. However, it is hard to apply and has been little used.

Empty homes also tend to be in areas of lower prosperity with fewer jobs and less housing demand. In the Northeast 1.4 per cent of the housing stock is long-term empty. In London it is only a bit over 0.5 per cent. The risk of using empty homes to meet our housing or immigration challenges is that frankly they’re in the wrong places for demand. There is already a phenomenon of former seaside towns being used, frankly, as dumping grounds for benefit recipients. I’m not an expert on immigration but I’m not sure exasperating and expanding this problem would play well.

Nevertheless, with long term empty homes increasing, what should government and councils do? First of all, it should define the opportunity properly and focus on long-term empty homes not the ‘headline’ figure.

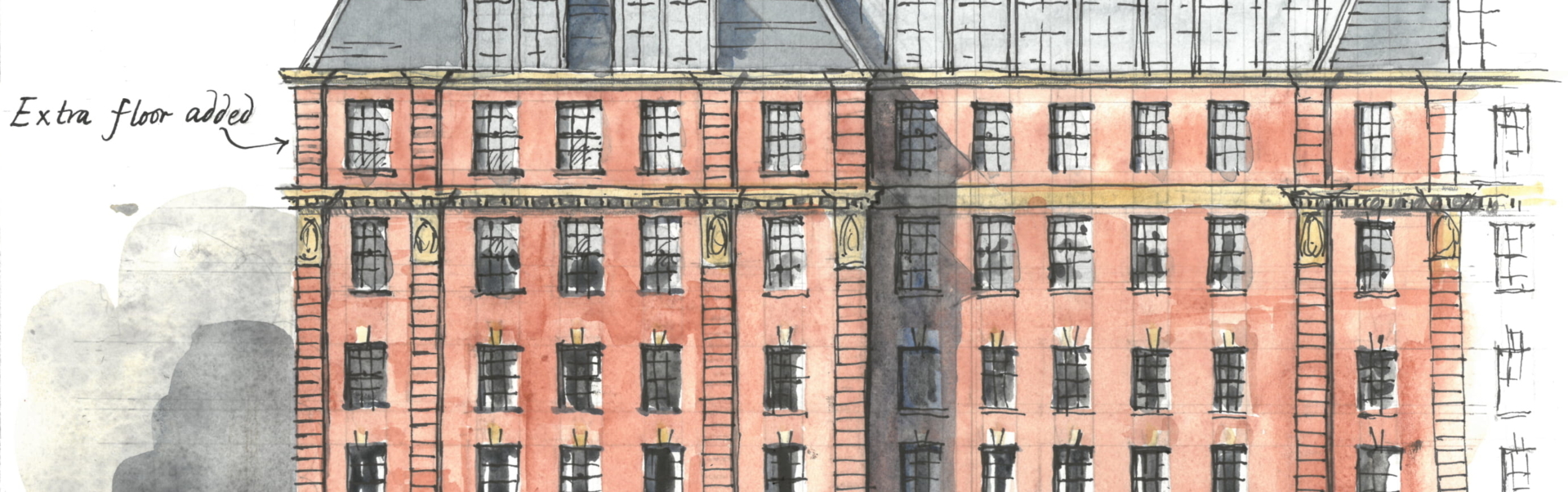

Helping and incentivising councils to get homes back into use seems very sensible. Tightening EMDO orders for extreme cases is wise. We can all support charities that help get existing homes back into use. Reusing an empty home is far more sustainable than building a new one and will normally make better use of existing infrastructure. It can be part of the journey to revitalising left behind towns. So, yes let’s encourage empty homes back into use. I would love nothing more than revitalised northern towns encouraging residents back into abandoned historic terraced homes. One good option is to make it easy for two, rather small, nineteenth century terraced homes to turn into one rather lager modern one.

There is an opportunity here. However, it is not equivalent in size to the size of our housing challenges. Anyone who thinks that filling up empty homes is the answer to our housing challenge is smoking something.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founder and chair of Create Streets