How we create new places and steward old ones to be beautiful and durable, happy and healthy

On Thursday, 5 June 2025, a carefully selected, invitation only group of landowners, council leaders, investors, architects and advisors gathered at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, in one of England’s most lovely places. We were the guests of Lord Salisbury and the Gascoyne Estate. We were there as part of the Create Streets Foundation’s Hatfield Symposium into how we build for generations. How can we create new places and steward old ones to be beautiful and durable, happy and healthy? One speaker kindly called our day, ‘a really really important event.’

No ‘dispatch from the front’ can summarise everything that happened. Everyone who came will have had different conversations and benefited from different insights. And I had to miss some portions of some talks whilst I was preparing my own sessions. Nevertheless, with all the usual caveats and apologies, here is my personal summary of some of the key points that were made during the course of a (certainly for me) marvellous and magical day.

- A Quiet Revolution is taking place in the quality and humanity of new developments. Although we are still pouring concrete and scarring our towns and countryside with ugly and unendurable places much of the time, more and more new places are humane, lovable and walkable. We are unlearning the mistakes of traffic modernism. Something has As John Simpson put it, ‘it’s different to 40 years ago. We are at the start of the new age of reconstruction.’ Chris Williamson, incoming President of RIBA, showed how much better was our approach to urban transport infrastructure than a generation ago. From around the world came uplifting and moving stories or rebirth and of the rediscovery of urban beauty: Dennis Pepke in Dresden and the spectacular recreation of Dresden; former mayor Jim Brainard and the re-naturing of ‘downtown’ Carmel in the US; Guy Courtois exploring the startling renaissance in urban design in some French towns, most notably Plessis Robinson where the population has tripled, the quantum of social housing remained identical and the quality of life been transformed; George Saumarez-Smith exploring the work of the Duchy of Cornwall and Adam Architecture in the UK. Anthony Downs and the work of our hosts in Hatfield. Across the world more and more places are being created or recreated with love.

Restitching Dresden: all this is new and would not have happened without 60,000 citizens insisting that it should

2. This is not just a Western conversation. In the premier of our film, A Quiet Revolution (made with The Aesthetic City), we saw mesmerising examples from Africa and from India of conversations about durability, sustainability, landscape management and urban health and beauty converging. For example, the Nubian Vault project has been reteaching and helping reseed traditional building skills so that local villages can themselves create beautiful endurable homes rather than relying on contractors to take their money and pour cement. Ten thousand homes have been built so far in a growing ecosystem of change.

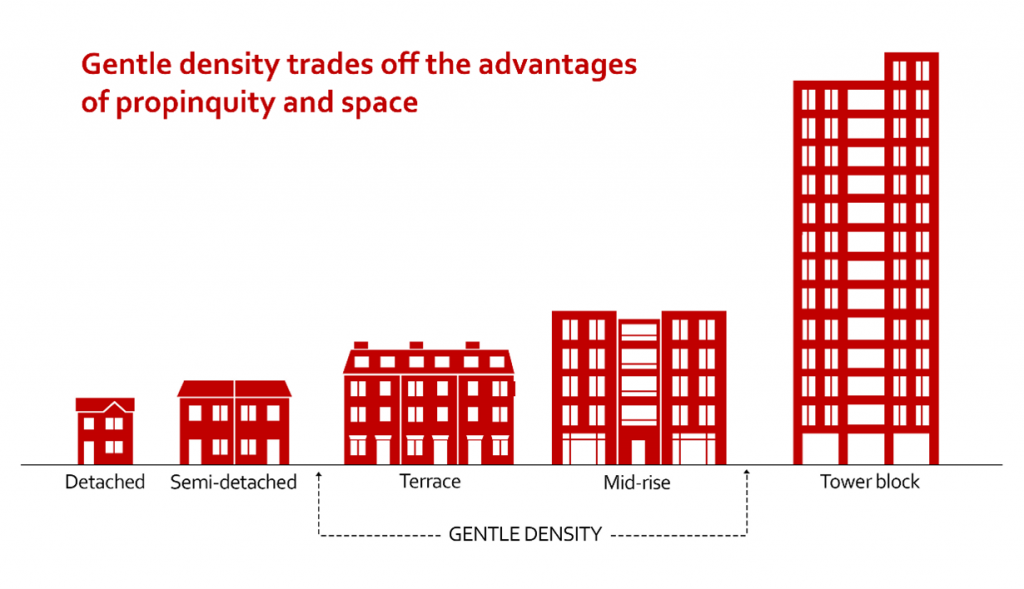

3. Place matters to economist and investors, not just designers. This is not just a conversation about architecture and urban design. As Mark Gregory, formally chief UK economist at Ernest and Young, put it ‘we lost sight of place but now we’re fixing that.’ Michael Gove also explored how the evidence is increasingly clear that ‘gentle density’ places people like are quite predictable for most people most of the time and are associated with better health and happiness, more economic agglomeration effects and higher land values. Victoria Hills, the chief executive or the RTPI, explained how growing regulatory costs are pushing development from low density to gentle density.

4. However, just because something is possible does not mean that it is easy. There remain many challenges of economics and of planning to creating better and more valuable ‘gentle density’ places. The prize is worth it but not always easy to obtain.

5. Trust the people to define place and identity. One theme that swam through the entire day was ‘trust the community.’ Everywhere we see a similar phenomenon. If you ask people proper questions about how people actually wish to live, you get very clear answers. Anthony Downs explored how the Gascoyne Estate’s work at Hatfield has been anchored in understanding local preferences leading to simple but delightful pattern books. Cllr Doug Pullen, leader of Lichfield Council, explored how understanding citizens’ design hopes and fears ‘unlocked’ a previously stalled site which is evolving from a car park to hundreds of beautiful new homes. Trusting the voters works: ‘I’m not an architect. I’m not a planner but I know a beautiful place when I see it’ was how Cllr Pullen put it. Dennis Pepke explained movingly how the renaissance in Dresden was made possible because over 60,000 citizens insisted that the city should be reborn, initially with resistance from city authorities and architects. Cllr Paul Harvey, leader of Basingstoke and Deane Council, made ‘the case for localism’ for design and development not ‘the long screwdriver trying to fix everything from Whitehall.’

6. Promote stewardship. And move from housebuilding to place-making. If we want people to ‘fall back in love with the future’ then new development should not make old places worse. Right now most think it does and will. Cllr Harvey called for ‘placemaking not conveyer belt housebuilding.’ As Michael Gove and Mary Parsons both explored, we will need more often to take a stewardship approach supported by long-term investment, not just short term housebuilding. Settlements should be renewed. New developments should be regenerative, enhancing the environment and adding to the health and biodiversity of their context.

7. Do design codes help? Most of the time, yes. Philip Fry, of CG Fry, was unconvinced. Since the work of the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission on which Mary Parsons sat (alongside me) design codes (or pattern books) have started to play a more prominent role in the English planning system. They are intended to ‘bring the democracy forward’ and set a really clear visual set of requirements for what is locally popular so that landowners and small developers have a clearer idea of what will, and what won’t get planning permission (you can see the newish national guidance on them here and some best practice tips here or here). My view, for what it is worth, is that they are essential when councils need to drive up the standards or when landowners want a wide range of builders and developers operating to their pattern. The very best architects and builders working with the experienced clients may not need them, but that depends on a relationship of trust and confidence which takes time to build as some of the early failures at Poundbury demonstrate. (Part of phase two at Poundbury was described as ‘a bit of an architectural zoo’ where design and build quality was lost in some places). Visual design codes, well enforced can win public trust: ‘design codes can help when they are easily understood by the developer and the public’ explained Cllr Pullen.

8. Where are the political challenges? How do we build more homes? What is the tension with quality? A common, though not universal, view from panellists was that ‘we have a broken planning system.’ New legislation will be slow to take effect and do we have enough law already? Much more use could be made of secondary legislation that already exists under the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act. (For example, here). Clare Mirfin spoke of one planning application with 570 documents within it. ‘Just loading it on the council website risked repetitive strain injury.’ We need a system which is ‘quicker, simpler, fairer’ as Christopher Boyle KC explained where ‘good ordinary’ locally acceptable development is de-risked. The good news is that is possible under the current system as Cllr Pullen demonstrated. However, it is far from the norm. ‘Can we get quality and quantity?’ asked Mary Parsons, ‘I think the answer is both but the risk is the quality.’ Victoria Hills was also worried that with the demise of the Office for Place, ‘who is holding the ring on design quality?’

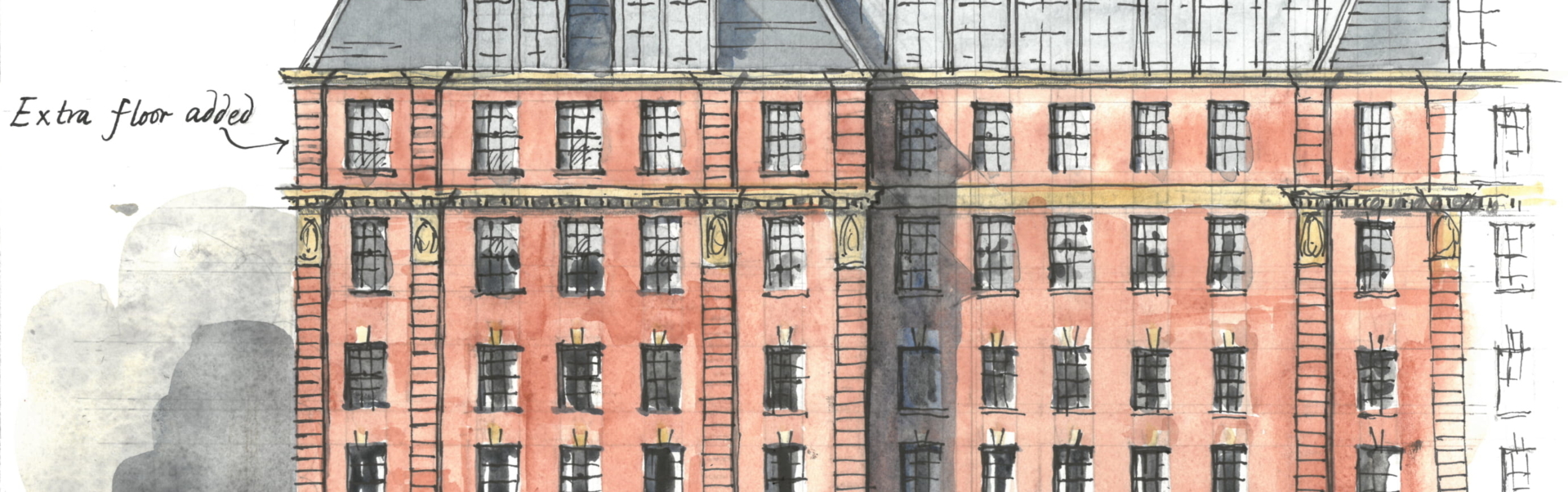

9. New towns or intensification? There was support for new towns, a desire to embed stewardship landownership models holding public land in their creation but also a concern that they would not be quick. ‘I have had a number of new towns “on the books” for 15 years,’ complained Christopher Boyle KC, ‘They have still not delivered.’ The fastest route to new homes will often be intensifying existing places by de-risking housing and ‘legalising housing.’ (More on this, here). But that does not mean that we should be creating new homes and, more usually, new urban extensions. Chris Curtis MP hoped that residents of this second generation of new towns would attend a similar conference 40 years hence.

10. We know how to do this in principle: the cook book for good places. The range of patterns that make it easier to create valuable and popular places is well established and evidenced How you deploy and deliver the pattern in a local place is of course the trick. Themes that particularly emerged during the conversations included:

a. Planting street trees and weaving urban greenery in streets and squares as Phil Askew and Billy Dasein and my colleagues Eleanor Broad and Ed Leahy explored. Here is our ‘bible’ on greening up streets, why, where and how!

b. Creating real middles with richly mingled uses emerged strongly from our international discussion and from our film, A Quiet Revolution.

c. Daring to make places attractive with anthropomorphic ornament and interest as Francis Terry explored. Emerging evidence from neuroscience explains why this matters for human interest. (For example, see chapters six and seven here).

d. But a ‘simple palette’ can work too as Anthony Downs explained of their work with Brooks Murray, with decent local materials, a strong sense of local place and good proportions. ‘I quite like normal’, added Cllr Pullen. ‘What do people like’ is a crucial question and don’t just trust planners or developers to understand the answer.

e. Creating public buildings early and to a high quality as they are doing supremely in Plessis Robinson. ‘Put public buildings first,’ exhorted John Simpson

A new library and theatre in a modest French town, Plessis Robinson

f. Deploying tricks like running the services down the parking courts around the back so that you don’t have to dig up the road for repairs has worked well in Poundbury and Nansledan as George Saumarez Smith explained.

11. It’s time for trams: transport matters. For larger or more urban developments particularly, public transport (and active travel) is crucial for creating sufficient homes at Gentle Density. ‘We are really terrible at this’ lamented Stephen Joseph. The evisceration of our trams in the 1950s and gutting of our railways in the 1960s was, in retrospect, a catastrophic error. Michael Gove mentioned Lord Beeching’s name and I added the shudder of a pantomime villain. Milton Keynes was approved apparently in the same week that the train line through it was cancelled. But transport should serve people and place not the other way around. As Chris Williamson memorably put it, ‘we shouldn’t use technology because we have it, we should use it because it makes cities more beautiful.’ Quite right.

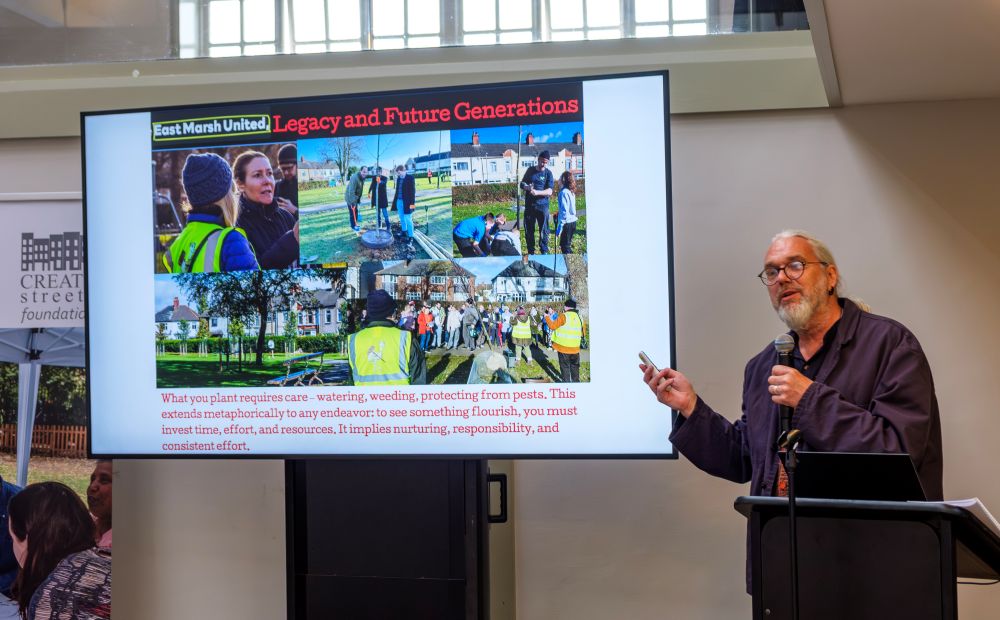

12. Above all, place matters. Place matters to our sense of ourselves. It affects everything from the air that we breathe to our sense of safety and purpose as we go around our daily lives. We want to feel proud of our homes. We need to. And, as Simon Jenkins reminded me, streets are crucial to good place-making. He is right. Towns needs streets that put people first not roads that put cars first if they are to flourish. My colleague, George Payiatis, spoke of the ‘frustrated pride’ of Chatham’s residents who are working actively to make their town better. It’s a concept that Create Streets often encounters. Chris Curtis MP, a powerful advocate for growth in the new House of Commons, rightly and passionately defended the qualities of Milton Keynes as a place to grow up and in which to live. Dare to respect emotion. Dare to create new and steward old places to be beautiful and lovable. Francis Terry defined a good place as ‘pleasant to be around, has good manners, cheerful.’ That’s not bad. Billy Dasein, Chief Everything Officer of East Marsh United, spoke movingly of Grimsby and the pride that he and his neighbours take in improving their slice of England: ‘this places is our place.. we did this. We put the trees in.’ Amen to that.

I apologise to those who insights and questions I have unavoidably overlooked!

Thank you to everyone at Hatfield for making the Building for Generations Symposium possible. Thank you to the Create Streets Foundation’s kind sponsors (Lightwood, C G Fry and Son Ltd, Pinsent Masons and Brooks Murray Architects) without whom it could not have happened. And thank you to my lovely team for the hard work, passion, common sense and good humour with which they pulled it off.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founder and chair of Create Streets