Nicholas Boys Smith in conversation with Create Streets fellow and Benghazi resident, Nada Elfeituri, and Create Streets senior urban designer, George Payiatis, about Create Streets’s support to the regenerative repair of Benghazi’s city centre

Introduction: a city with a rich history but recent challenges

Nicholas Boys Smith: Nada, George, it’s lovely to see you both through the magic of Microsoft Teams. It was obviously great fun working on this project. Nada, tell me about Benghazi, the city as a as a place to live and work today. What’s best about it? What are its challenges as a citizen, as a Benghazian, is that the right term? What are your hopes for its future?

Nada Elfeituri: We use the term Benghazino! It is an old city. It’s a city with a lot of history, a lot of heritage, but also a lot of battle scars. It’s a city that’s seen colonisation at its worst. It’s a city that’s rebuilt itself over the centuries. Through the different periods of history, people have added to it. It’s been shaped by the community. In Libya, Benghazi is known as a bit of an outlier as a city because there’s no one tribe that’s from the city. No one is from here, but everyone is from here.

It’s a city that has the highest representation of all the tribes and all the social factions of the country living side by side together. That’s what makes it so beautiful, the pluralism of the city. I think it’s a beautiful city as well. It’s located on the Mediterranean, it’s got these seven beautiful lakes. So it’s also called the city of the Seven Lakes. It’s a fun place to walk around, to spend a day. Fantastic weather, a lot of the time.

The biggest challenge has been the changes over the past few years since 2011, the revolution, the war, trying to live within a city that’s constantly transitioning. That’s what’s been so interesting about the project: how do you design a city that’s constantly in flux on a historic level?

What will the future hold?

Nicholas Boys Smith: As a Benghazino, if I’ve got that right, what are your hopes for Benghazi’s future? Fast forward forty years: what would you like to have stayed the same? What would you like to have changed?

Nada Elfeituri : My main hope is that we can begin addressing the chronic challenges we’re dealing with as a city that’s growing very rapidly. After 2011, there hasn’t been a lot in the way of controlled urban growth. It’s just been very car dependent sprawl. If you look at the suburbs of the city, it’s very different from the city core. We’re starting to see more gated communities. I’m worried about the city going in that direction.

What I hope for the future is that we’re going to have accessible public transit, that we’re going to have walkability in every neighbourhood, that we’re going to see more and more greening initiatives. We’re starting to see it now: the importance of having more greenery in the streets.

But I would like to see it everywhere, because like most cities, Benghazi’s also facing issues of inequality. West Benghazi is more affluent, more thriving than East Benghazi. I’d like to address some of those gaps.

The municipality’s been doing a great job with accessible public space. They’ve been doing a lot of park projects. I’d like to see more of that. I think the problem with the way we’re doing urban design is that we’re seeing public space as a finished product. “I’ve built this park, that’s it.” But the park needs maintenance. The park needs to adapt to the changing needs of residents over time. I’d like to see urban design as a project that continues rather than just these one-off interventions.

What was the project?

Nicholas Boys Smith: That’s a very eloquent description. George, tell me about what the project was, why Create Streets got involved, what the aims and hopes were, who we worked with.

George Payiatis: We worked with the World Monuments Fund, who often work in post conflict situations to preserve the built environment and with Fadlallah Dagher, a heritage architect and urbanist based in Beirut. Having Nada as a former Create Streets colleague, we had a direct connection in Benghazi. It was really important to have that presence on the ground and be working with someone who understands the place.

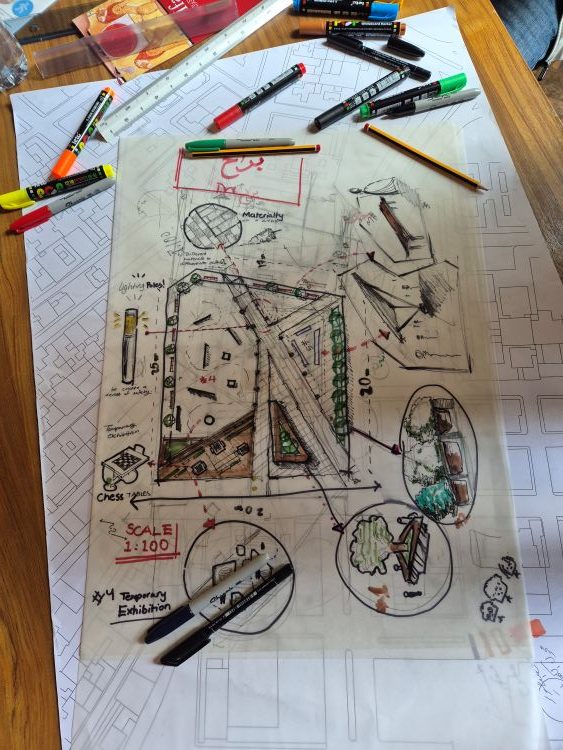

The purpose of the course was to provide training to support the restoration of two war damaged heritage buildings: an Ottoman Mosque and the old Italian town hall. Nada and I were focusing on the restoration of an underused public space in the heart of Benghazi’s historic centre while Fadlallah led on the building restoration. Currently a bit of scrubland, a surface car park, this space has the potential to be something far greater, particularly given its relationship with the Barah Culture and Arts Centre.

Our remit was to develop plans for tactical interventions to bring that space to life and serve as a model for future conservation and development. We had 22 participants. Twenty of those joined us in Cairo for the in-person workshop.[1]

The syllabus included three online sessions and one in person session. Session one was an introduction to urban design, the basic principles of place-making, presenting studies of tactical urbanism and the design process. Our second session looked at how to develop context analysis and sketch designs. Then we had a vision workshop to get everybody on the same page for the site. They were all run online and hybrid with me over here and led by Nada on the ground in Benghazi. The course culminated in an in person co-design workshops and site visits in Cairo.

It was wonderful to meet the participants and see them getting to work sketching and designing in person. We visited some similar projects within the old historic Mamluk city to see how architects and community groups had re-greened their streets and brought some under-used spaces back into active use.

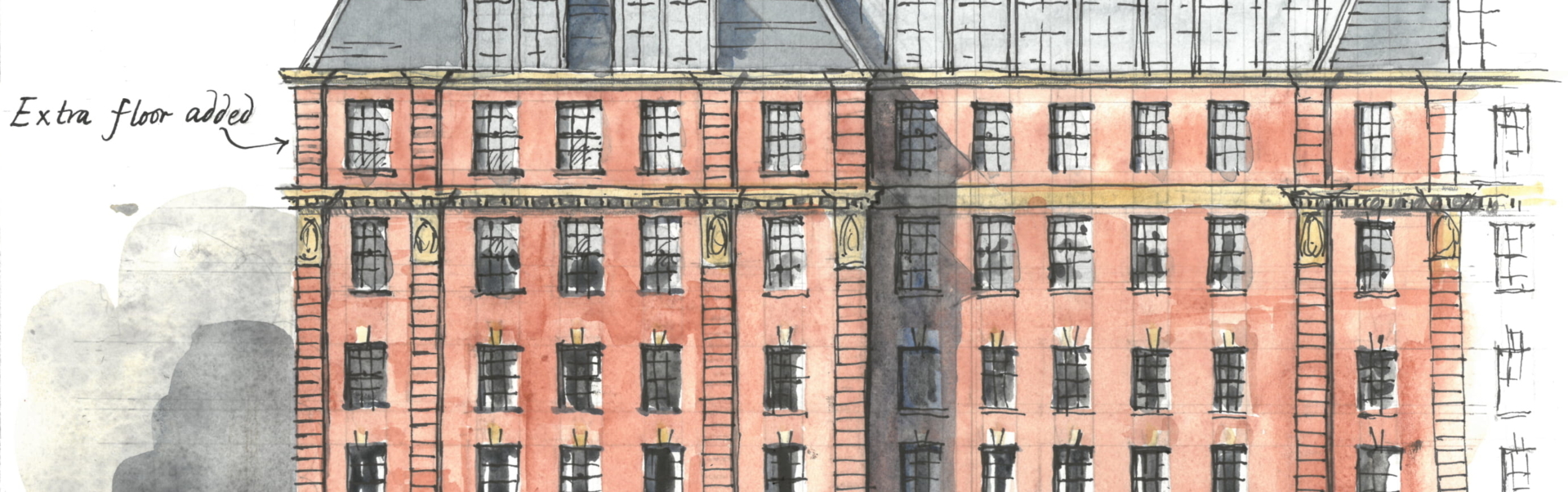

Whilst Nada and I were focusing on urban design and street design, Fadlallah was leading the heritage conservation sessions which looked at how you analyse historic buildings,. Recording what’s there properly, making use of the historical archive before those buildings are potentially further damaged.

The area of our study is really interesting with so much potential development in the next few years. The city is in flux. Our course developed a high-level site vision which could be achieved in shorter, incremental steps. That’s why tactical urbanism was a was a focus.

Our study site in the heart of historic Benghazi

A wholistic approach to heritage

Nicholas Boys Smith: A very Create Streets point! Have a clear vision and practical things to do in the short term. Thank you, George. Nada, who came to the workshops? What were their hopes and aspirations and where were the points of tension?

Nada Elfeituri: This is where this project was really significant. We brought together folks who work in the municipality of Benghazi, the Project Office who are already engaged in doing public space work. We brought the Urban Planning Agency, which is responsible for creating guidelines for how things are built. We brought the Historic City Authority. We brought students from the university. We brought young architects. We brought artists from Barah. What’s significant is that these groups of people normally do not work together. Siloed work is very much in play. For us to be bringing those groups together was a great step forward. And they did work well together. There were no issues. We could see how the different groups complemented each other’s expertise and knowledge.

For example, the municipality brought in their infrastructure background. What helped was that they were all unified in their goal to see their city improve. They all want to see more sustainable practises around urban design, development and heritage. In our first introductory call we were asking what folks would like to get out of this project. They were all saying we want to protect what still exists and we want to make the city a place for everyone. That unified view helped.

George Payiatis: I was going to add to Nada’s point that in a room of 22 people to arrive at consensus at the end of the process is really quite significant: preserving heritage, greenery, accessible space, places for children’s play, spill out space from the surrounding arts centre, activation of that space. Those principles were embedded within each of the sketch designs. It’s just wonderful how that’s come forward into a cohesive plan for the place. People might disagree as to where a specific thing might go, but the overall vision was similar. And that was the case from day one.

Of course, work being siloed is a challenge that we experience in our work over here as well. It’s something we’re all familiar with.

Nicholas Boys Smith: Yes, Benghazi is not unique in that! Specifically on that point of the interaction between urban design and heritage: something I’m very interested in is trying to help heritage professionals realise that urban design and street design really matters. It’s all very well to restore the shop front. But if the pavement is only five inches wide and the cars are zooming past at 40 mph, the shop front may look nicer, but it isn’t going to work. Were there any moments of mutual interaction and learning on this type of points? Or was that asking too much?

Nada Elfeituri: When we expanded the definition of heritage, it helped bring in the engineers and the architects and the urban designers, not just the heritage experts.

When we talk about heritage, we’re often talking about a building, a church or a mosque or whatever it is. What’s interesting about Benghazi city centre is that the entire area is classified as a heritage zone: it’s the street pattern, the functionality and the arcades and how they deal with the climate. Once we expanded that definition of heritage, it helped bring everyone together to see how heritage and urban design was working together.

Making hybrid work

Nicholas Boys Smith : A technical and a process question. George, how was it co-running a workshop remotely when nearly everyone else was in the room? Was it ‘Back to COVID’? Or did it work? I would imagine it was quite hard: trying to keep up with, I mean that is a fast brained individual like Nada within a conversation largely taking place in Arabic.

Any reflections on what it was like to be sitting in a sitting room in north London as half the conversation takes place in, in North Africa?

George Payiatis: The main challenge was not meeting the group in person early on in the process. Due to circumstance, we all met once the course was almost at its closing stages, I think it’s always nice to meet those with whom you’re working with as soon as possible.

When it comes to the actual hybrid sessions, my experience is that it can be challenging when someone is chipping and they’re not in the flow of the conversation. But it was well structured, Nada was taking me around the room on the phone, looking at people’s work as it was developing. But, there’s no substitute for being there in person, seeing the plans come to life and hearing those conversations as they’re taking place. Given the set up, the physical separation and distance, I still really felt involved in the process. The students were clearly very engaged and really eager to kind of get going with their plans and their proposals.

Nada Elfeituri : I just wanted to add what was it like to use a hybrid approach for us in the room. Libya’s been isolated from the rest of the world for a very long time, not just the past 14 years but during the Gaddafi era as well. Having people from other parts of the world there with us, even virtually, in the room was such a big thing. It’s so important for Libyan communities to feel that they can be connected to the world, to learn from expertise in other places. So, even though it was virtual, it was important to hear about Create Streets’s experiences in other countries and then to get your take on what we could do with our space. Having that connection with the rest of the world, even digitally is super, super valuable and important for us.

We took a hybrid approach to the first three workshops.

Visiting Cairo

Nicholas Boys Smith: That’s lovely to hear. Thank you very much. Moving from the virtual to the practical. Nada, please can you tell me about how all the threads came together in Cairo: the series of workshops, the visits. I was very jealous looking at some of the photos. How did that work? What conclusions were reached?

Nada Elfeituri: The trip itself to Cairo was fun from the beginning because most of us were travelling together from Benghazi, from that that moment we all met up at the airport. It was fantastic to get the momentum going. Everyone was excited to see what examples we could learn from in Cairo. A few of the participants had been to Cairo before. It’s a similar context, but also very different.

Then we were in this beautiful venue, this beautiful space in the French Institute. We were picking up on the threads of where we left off with the heritage training and the urban design training, combining those together into the four days in Cairo to talk about next steps. There was a feeling of, “OK, this is real. We’re actually going to be designing and implementing this park.” This is the moment where people took a step back and asked, “What does it look like to be really implementing this, this on the ground?”

Another thing I want to bring up is that the initial plan was to do heritage training with a set group of participants and then urban design training with another group of participants. The big group was initially divided into two and at one point we thought, “No, we should combine these two groups and start blurring those lines.” We wanted it to feel like it’s a continuation. We’re talking about heritage in an urban space. What does it look like to work on those two tracks together? Ultimately that was a good decision.

In-person design workshops, Cairo (December 2024)

Now make it happen: next steps

Nicholas Boys Smith: What’s what, what is going to happen next to those buildings, to that park? Is the funding in place? Is momentum continuing. What your prognosis for the months and years to come

Nada Elfeituri: Another great outcome from the workshop in Cairo once we created that final plan was that people were volunteering for different roles. Someone was saying, “I would love to take this forward and turn it into a finalised design.” Some was adding, “I would love to work with you.” Someone from the municipality said, “If you need any permissions. I’ll be sure to get them for you.”

So, once we came back to Benghazi, we already had a list of who was going to work on which phase. At the moment we have a near finalised design in AutoCAD. We want to come back with all the participants, refresh everyone’s memories and then refine it a little bit more. We have requested the final funding to do the actual implementation. So, what we’re hoping for is to begin making the park in the next month or so: getting all the materials, working on the art pieces that reflect the site’s history and heritage of that site. It’s a parking lot now, but it used to be an important building that was razed. We want to bring some of that back.

Nicholas Boys Smith: I was in Somerset House in London yesterday the marvellous William Chambers building, which for many, many years served as a as a car park. It’s now been brought back as a marvellous public space. Self-evidently Birmingham and Bristol and Benghazi are not the same but more of the challenges rhyme than you might anticipate: issues of parking, issues of public space, issues of safety. Yes, they pan out very differently, but they’re more recognisable than distinct I believe. Our common humanity has more in common than our distinctions. That’s my experience anyway. George, any final thoughts on sort of what happens next? Obviously, it’s very much up to Nada and her compatriots to drive it forward. Is there anything we’re hoping to support with here in London. Do we have any other thoughts or similar projects in the future that we hope to take forward?

George Payiatis: More broadly, the work that we’ve done, the syllabus, that we have worked up is replicable elsewhere. This is very much not us telling people how to do this and that. It’s about sharing what’s worked and what’s worked less well elsewhere and, as best we can judge, why. It’s helping people shape their vision for a place into something that’s deliverable. No one knows an area better than those who live or work there. But there’s still a role to share relevant experiences and suggest decision-making frameworks which we can play.

It would be absolutely wonderful to do similar work elsewhere whether it’s in North Africa, the Middle East or Europe. There are plenty of discussions we are having. On this project specifically, it’s hugely exciting, as Nada says, that those plans are being worked up. It would be so absolutely wonderful to see, a sketch that was on tracing paper a couple of months ago pre-Christmas actually delivered as something tangible on the ground. The energy, the enthusiasm, the talent, the ability of that, that really varied group was absolutely wonderful. If we can see something delivered on the ground and if it’s something that we can visit in the next couple of years, that would make me truly happy.

Work is already underway to turn the sketch plans into a reality in the coming months.

Nicholas Boys Smith: Amen to that. Nada, any final thoughts?

Nada Elfeituri: One valuable addition is that tactical urbanism is not a new thing for Benghazi. There are instances of people using a public space and then the authorities coming in and turning that public space into something more formal: a walking track that was created in a place that never was never meant to have a walking track, but people were walking there and so they begin adding the infrastructure. I think what we helped do was validate tactical urbanism as an approach for architects, because it’s definitely not something that’s being taught in architecture schools. How do you create something out of what people are already using or already doing? Just seeing how something temporary, very makeshift could turn over time into something more permanent. I think that was incredibly helpful in terms of mindsets of the engineers and artists that we were working with. The ultimate hope is that this tactical park that we’re doing is going to turn into a more permanent space. That would be fine.

Create Streets worked on this project alongside the World Monuments Fund, Barah Culture and Arts Centre, the Historical City Administration Authority of Benghazi and Fadlallah Dagher, a Lebanese based heritage architect. You can read more about the project here.

[1] Foreign Office travel advice and available insurance means that British citizens are not able to travel to Benghazi.