Nicholas Boys Smith visits the new British Memorial in Normandy

I was nervous of visiting the new British Normandy Memorial at Ver-sur-Mer. I was unconvinced by the need for it. Surely, there is one already, the British cemetery and memorial at Bayeux, where 4,648 young men lie forever and where over 1,800 more, whose bodies were never found, are carefully commemorated?

And I was nervous of its spirit and design. Can anything improve upon the quiet and moving gentility of the Commonwealth War Graves? Every year, I am lucky enough to visit Normandy en route to my French in-laws. Every year my two boys and I, toddlers when they started, teenagers now, visit the tiny British cemetery at Secqueville-en-Bessin, literally a corner of a foreign field that is forever England. It is our annual pilgrimage. 117 young men, of whom 18 are German resting in a little beech-girt garden in a French field with the wind blowing, the yew trees growing slowly and the skylarks and swallows diving and dancing, singing and swirling overhead. How might any modern memorial, compete with such understated and bucolic beauty? Surely today’s tendencies to mawkish overstatement and to overly self-conscious emotion would feel crudely vulgar in comparison? I had read that the memorial was temporarily surrounded by hundreds of silhouetted figurines of fallen soldiers, a self-proclaimed ‘people’s tribute.’ Surely this is just all too much? Less British, more American; less home counties, more Hollywood?

You can tell that this is a modern memorial. There is ample parking. Benches are sponsored. (Though, thankfully, by commemorative groups not by corporates). And, as you progress from the parking ground to the memorial, a series of stone plinths tell the story of the battle of Normandy.

And yet I was wrong. This memorial was necessary and is well and wisely done. On the August day when I visited, it is busy. And not just British visitors. My row of the car park had seven French, three British, one Belgian and one German car. No Normandy war cemetery that I have ever seen is so replete with people. This matters. And those explanatory plinths as you walk towards it, one side in French, one in English? They would have been too much 60 years ago. But they are perfectly necessary now. We cannot assume that today’s youth or those 200 years hence will intimately know the story as they did in the 1950s, 60s or 70s. The generations are passing. Already other than a few extraordinarily long-lived men who were little more than boys eighty years ago, D-day has passed from living memory.

What of the memorial itself? It is perfectly judged and immaculately situated.

Behind it, the wide expanse of the English Channel stretches to Dover and to Portsmouth. Below it lies King Sector, Gold Beach where the 6th battalion The Green Howards and the 5th battalion The East Yorkshire Regiment made landfall at 07:25 on 6 June 1944. To the north-west, clearly visible, lie the corroding and scattered remnants of the Mulberry harbour off Arromanches, that miracle of American know-how and British ingenuity which survived the great storm of 19 June 1944 and from which and by which the tanks, troops, and transports, food and fuel landed which were to liberate Western Europe.

The British Normandy Memorial as approached from the sea

Behind the memorial, a reassuringly figurative statue of British soldiers running ashore is comprehensibly human. Three comrades, with rifle, Sten and Bren gun, scramble uphill where their living and breathing corporeal predecessors really ran up the slopes from Gold Beach.

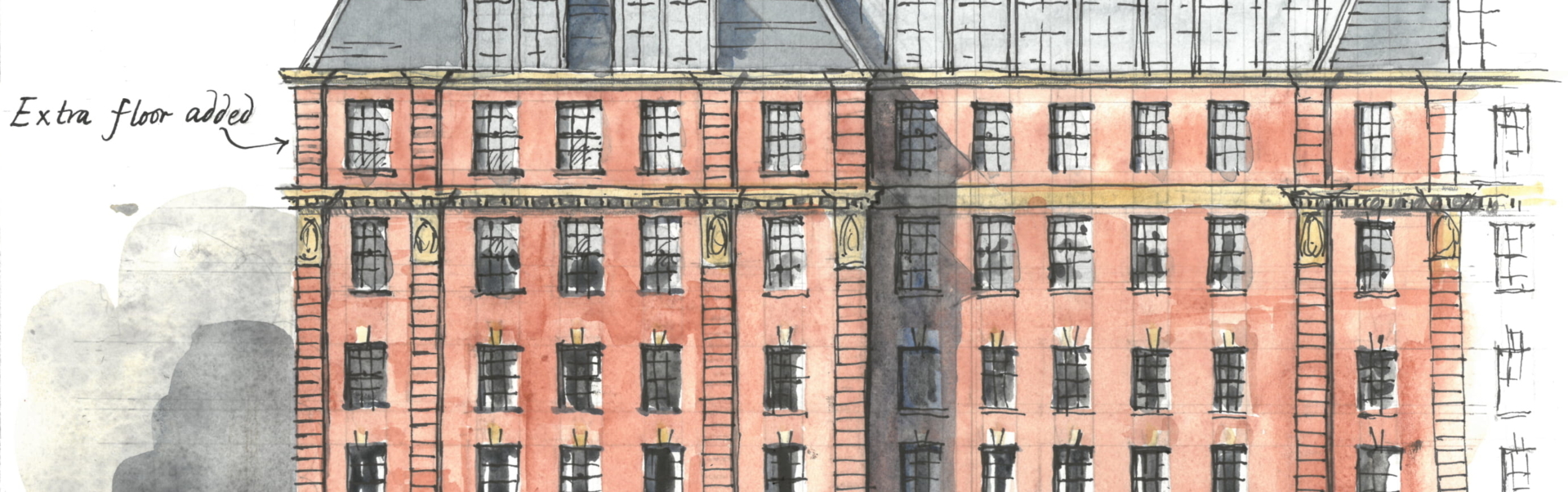

The main memorial, by the important British Architect Liam O’Connor, is not in competition with the Commonwealth War Graves but in communion with them. White Burgundian limestone. Stripped doric pilasters without plinths but with cleanly simple capitals. Understated twentieth century classicism. It is less Christian than its predecessors. No Cross of Sacrifice, combining sword, Latin crucifix and Celtic cross here. But it is no less sacred. The inscriptions, perhaps slightly too many, are nevertheless exquisitely chosen. In the entablature are etched the words of the Allied Commander on land, Bernard Law Montgomery; “To us is given the honour of striking a blow for freedom which will live in history and in the better days that lie ahead men will speak with pride of our doings.” The proof lies all around.

The central structure is bold, simple and pure, not the equal of Lutyens’s cenotaph but in the same austere and affecting spirit and with comparably subtle nods to classical antiquity which most of us cannot directly anatomise but can nevertheless comprehend. When it comes to creating holy places, and this is a holy place, then structures need to have purity but also serenity, comprehensible coherence but also unknowable mystery. They need to be not of this time but for all time. This memorial rises to that high purpose.

A pergola of limestone columns processes around the memorial’s four sides forming an open cloister, half Surrey garden and half monastic ambulatory. On it, recorded day by day and service by service, are etched the names of the 22,442 men and women under British command who fell in the three months from the sixth of June to the 31st of August 1944. Arranged not randomly where they lie or alphabetically on a wall, this colonnade feels less like a gazetteer of loss and more like a story, an invitation to research and to wonder. Where did these people come from? How did they die? Alone or with comrades? What might they have become? Are they still remembered?

The limestone pergola etched with names: part Surrey garden, part monastic ambulatory

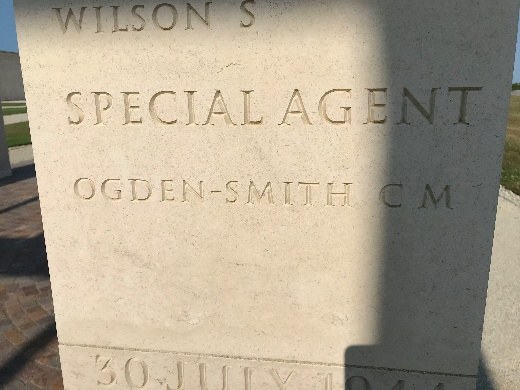

Indeed, as I wonder around, other visitors, iPad in hand, are seeking individual names in the pergola, finding them, touching them, pausing. Drawn to a name on its own, I looked up “special agent” C M Ogden-Smith and read of Major Colin Ogden-Smith, one of the very first to volunteer for the newly formed Commandos in 1942 and who subsequently served with SOE and then the little know ‘Jedburghs’. Parachuted deep behind enemy lines into Brittany on 9 July 1944 to lead sabotage and guerilla warfare, his band of the maquis were betrayed three weeks later. He was killed in a firefight with over 70 German troops, leaving a widow and baby daughter. He and the Frenchmen with whom he died, are commemorated to this day in the Breton village of Querrien where they fought and fell.

Major Colin Ogden-Smith. One of the little known ‘Jedburghs’ who fell alongside his French comrades and who is commemorated to this day in the Breton village of Querrien

Even those who survived, often used themselves up in war unable to settle or to flourish. Best known of the men who landed on the beach below the British Memorial is Company Seargeant Major Stan Hollis of the Green Howards who won the only Victoria Cross awarded on D-Day but who struggled after the war. He died, aged only 59, in 1972.

An auxiliary memorial commemorates the French men and women who suffered so terribly in the battle. The bilingual inscription explicitly recognises not just the lost lives but the physical and emotional weight when a home becomes a battlefield. The family home of my wife’s grandmother was just outside Caen. It was so thoroughly shattered into irrecoverable fragments by the terrible RAF bombardment unleashed on 7 July 1944 that its very traces in the land could no longer be discerned. My mother-in-law still recalls visiting the city in 1950 and being able to peer into ‘cellars with the light coming in’ serving as homes to hundreds of house-less families. As she, in turn, ages it is a memory and an image that returns to her increasingly frequently. War casts long shadows.

French lives and homes were also shattered: the memorial to the French

After the clean and coherent perfection of the memorial, business as usual reasserts itself in the, rather crassly and obviously named, Winston Churchill Visitor Centre, not by the same architect. It is a parody of “contextual in name only“ design: exciting shapes, sheaved in charcoal black planks of wood, a building whose form, tone and materiality has precisely nothing to do with its Norman context. It recalls neither Normandy nor England nor the sanctity of sacrifice.

The best that can be said for it is that it is inoffensive and quickly driven past, tucked away as it is on the wrong side of the car park. The best that can be hoped for is that it will not last. Doubtless, pages of guff were scrawled justifying the building’s sustainability but it will need replacing within two generations. I doubt if it will last 50 years. It is sponsored, so the sign assertively tells us, by BAE systems. Their money was misspent. Three of the four urinals in the centre’s lavatory are already broken.

So yes, the British Memorial is a modern memorial: less understated and with more heavy-handed signage than its predecessors but it is busy, it is beautiful, it is sincere and it is understood. The surrounding clutter is distracting but the memorial itself is expertly judged and exquisitely designed. Its siting, above the beaches of the battle’s inception, is profoundly moving, as perfect a location as any religious structure anywhere in the world. If you are in Normandy, in fact if you are in northern France, come to this place and give thanks to those who fell and be grateful that we are still able to commemorate them.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founding chair of Create Streets