Nicholas Boys Smith argues that the Athenian authorities should be bolder

Life and a conference took me to Athens last week. Reader, it is true: international conferences are not quite a jolly, but they are jolly good fun. You get to say what you’ve said before to people who’ve not heard it before and, if you’re lucky, you can squeeze in twelve hours of tourism at the end at no personal expense. I know I always try to.

But visiting ancient Athens is ridiculous. Take the Agora, once the ceremonial and commercial heart of Periclean Athens. Now, a scatter of stones and marble in an olive grove. Pounding heat. Confused tourists scuttling from shade to shade, quickly ceasing to read the signs. To ‘discover’ archeologically the ancient Agora, 400 buildings were demolished. What’s left is more akin to post war Dresden then to ancient Athens. It’s a battle scene with trees not an educational experience. Fragments of conversation drift pass. “What do you think of this Greek stuff? “Emm. What’s next?“ “Zeus something.”

You get a better sense of ancient Athens in the nearby old town on the Acropolis’s slopes. Here the shops, narrow streets and pretty buildings with their colourful shutters and awnings are more reminiscent of an ancient colonnade or agora than any pile of clean, white stones in a hot, dry field.

Tourists make for two places in the agora: firstly, for the Temple of Hephaestus a remarkably complete ancient temple which survived because the Byzantines were sensible enough to make it into a church. Tourists shelter in its shade and take photos.

They also head for the roofed and remarkably complete Stoa, or covered market, of Attalos. Here, suddenly ancient Greece comes to life. The heat recedes. The shade and the cool wind rustle through the columns, replicating the civilised pleasures of ancient urban existence. Children lie on the marble for the cool. Visitors sit on the step under the fluted Doric colonnade and watch their fellow tourists pass by. Unconsciously they are echoing precisely the behaviour of ancient Athenians, meeting, talking and simply being in their town square.

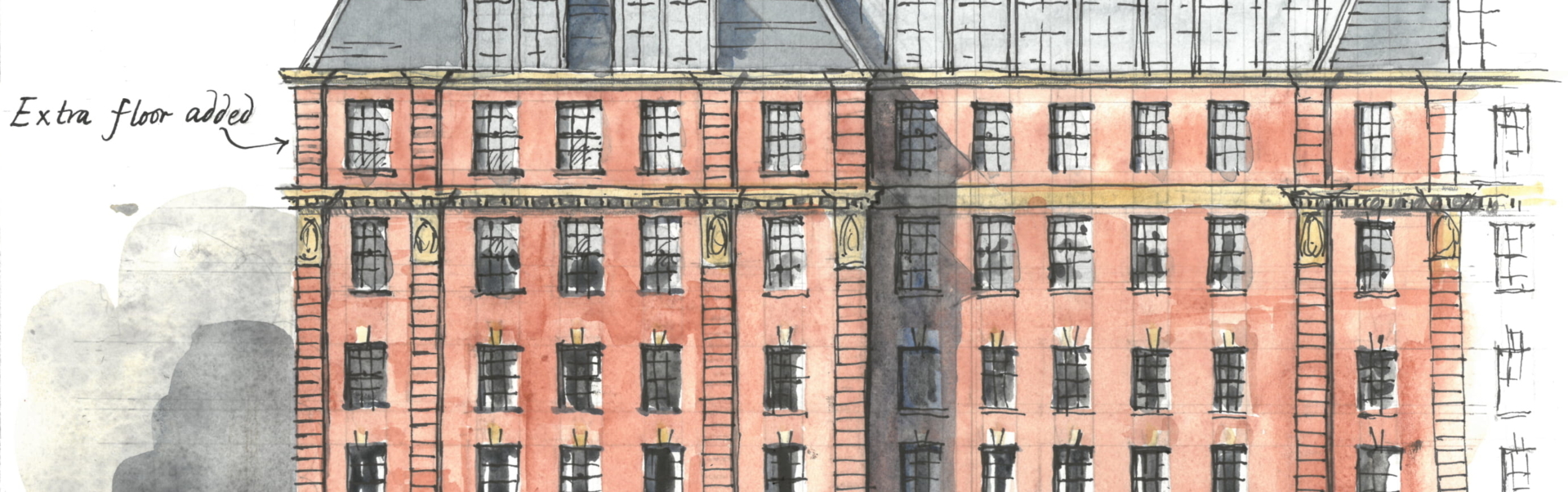

The guidebooks, or my guidebook at any rate, coyly tell their readers that the stoa was ‘restored’ in the 1950s. This is so inaccurate as to be a lie. The stoa was not restored. It was completely rebuilt to plans drawn up by the Athenian architect, John Travlos.

Travlos’s designs copied the partially surviving northern end, re-incorporated original stones found scatted about the site and, as best it could, followed the archaeology. However, nearly all of what you see today is modern. Many details they had to guess. Not one roof tile, not one truss, not one column, none of the supporting arcade is antique. And yet this is where the tourists come for the shade, the comfort and for a far, far better sense of the past.

It was built fast as well. A limestone quarry in Piraeus and a marble one in Mount Pentelicus were reopened in 1953. 150 masons, carpenters and workmen were employed. And in three years it was unveiled to assembled archaeological and Greek panjandrums.

Mr Travlos has shown what do. Clearly, we should rebuild what we can of ancient Athens. The land has already been investigated and scraped over for over a century. None of the site’s outlines or piles of stones need be lost. All original materials can simply be reincorporated into recreated arcades, temples, walkways and streets.

This would create work for Greek workmen, would doubtless attract donations and support from around the world and would deepen our understanding of ancient Greek building techniques by obliging emulation, just as we learnt from the 1950s erection of the Stoa of Attalos and as we are currently learning from similar projects around the world.

Tourist visits would skyrocket. And instead of sweatily failing to imagine an ancient city in a modern olive grove they could wander around an excellent imitation of ancient Athens buying food and souvenirs.

The Athenian authorities have always agreed in principle. The temple of Athene Nike on the Acropolis was completely reconstructed in the 1840s, a fact unmentioned in my guidebook. And, at present, new marble and reconstituted stone is replacing lost or damaged portions of the Acropolis’s Parthenon and Erechtheion temples and its Proplyaia, or entrances. It is impossible to tell by eye which of the Erechtheion’s ionic columns is modern. Though the fresh new slabs of marble throughout the Parthenon and Proplyaia are visibly whiter.

Given a choice, tourists much prefer the rebuilt monuments. Dozens take photos of one ancient theatre, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, cut into the Acropolis’s sides. Few are probably aware that nearly all of the seats they are photographing date from the 1950s. The other, unrestored, Theatre of Dionysos seems less popular. It was deserted when I visited.

For all the rebuilding the Acropolis is a fake experience. To understand what ancient temples were really like, you need to imagine something far darker and more colourful. Lawrence Alma-Tameda’s exquisite painting, Pheidas and the Freize of the Parthenon, probably comes closer. Or there is a concrete reproduction of the Parthenon in Nashville in America, complete with roof and an appropriately gaudy and gold leaf statue of Athena. Better still, visit one of Athens’ jewel-like Greek Orthodox churches. They are, after all, in direct and unruptured succession from the Byzantine empire. Inside, they are ornate, luridly coloured, elaborately decorated and dark, kept blissfully cool not by air conditioning but by their height and artfully created currants or air passing through them. This is closer to the real temple experience than shuffling round the outside taking photographs.

Perhaps the best argument against rebuilding ancient Athens is not the tourists’ wellbeing or comprehension but their sense of purpose. For there is a religiously ascetic component to ‘doing the ruins.’ If it is this hard and this unpleasant physically then in some mysterious way, it must be doing us good. This is modern tourism as medieval pilgrimage. From the hardship of the journey flows the virtue of the trip. Perhaps Athens’ thousands of visitors would feel cheated if their visit to the ruins was too easy, informative or interesting?

So let’s compromise. I suggest that Athenian authorities continue to reconstruct the Acropolis but allow it to stay white and fake and tough to visit, history not as comprehension but as penance.

However, they should rebuild perfectly every building and street and colonnade in the agora and plug them prosperously and enjoyably into the surrounding city, filling the whole recreated neighbourhood with shops, specialised museums and detailed immersive experiences so that tourists can really imagine and understand living and being in Ancient Athens.

What would Athenians say? My few conversations were encouraging. I ask one what he likes most about Athens? “Plaka, the old town. You have narrow streets and beautiful old buildings. I feel like I am on vacation. I go there to walk and relax and buy food things and street food. I wish Athens was more like that.”

They should make it so, for the good of tourists and of Athenians

A shorter version of this article first appeared in Unherd on 23 June 2024.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founding chair of Create Streets