Tom Bage is a Bow resident.

The inclusion of a paragraph on mansard roofs in the new NPPF is welcome news for the millions of people living in pre-1918 properties who would like a little more space or a greener home.

I live in Bow, where different groups of residents have spent nearly a decade campaigning for the freedom to add mansard extensions to properties in the area.

It’s been a circuitous process which illustrates why only political action from the centre can unlock a sensible mansard extension policy. And it shows why the government must go further in the NPPF to ensure residents in conservation areas can build mansards too.

Anyone who follows the work of Create Streets will be familiar with the multiple benefits mansards can bring.

With the right design guides, they are an historically appropriate architectural option, favoured by the Georgian and Victorians who built so many of the UK’s historic buildings.

For families like mine they could offer extra space to help us stay in the area as our kids get bigger – but for other neighbours it’s about allowing intergenerational living, making pre-war housing more energy efficient or creating a home that can adapt to a world of hybrid working.

The fact a more liberal approach to mansards could also help reduce rents and play a small part in reducing housing demand elsewhere (by gently densifying urban streets) is even more reason to support it.

So far, so simple. But, as Samuel Hughes sets out in “Living Tradition”, a quirk in our planning system effectively prioritises the preservation of frontages frozen in the mid-20th century over the housing needs of today.

In good times, putting rooflines over residents and parapets over the needs of people could be seen as just a peculiar case of British eccentricity.

In the midst of a housing crisis – when we have a traditional architectural option widely used by the Victorians who built the homes in question – it starts to look like a mistake in urgent need of a fix.

Mansards in the East End

Despite the fact that some buildings in Bow have Victorian-era mansard roofs, new ones are generally considered by heritage officers to be detrimental to the valley roof style seen in parts of the area. The creation of conservation areas in the 1990s, which cover most of Bow’s terraced housing, restricts the chance for sympathetic improvement of these buildings even further.

And on terraces with “gap teeth” (where the odd house had added a mansard before restrictions came in) our current rules do not allow for additional mansards to be built, meaning there’s no immediate chance of the sort of even rooflines many planning authorities favour.

However, following a lengthy but ultimately successful campaign by a former Bow Councillor planning guidelines were updated, and in 2017 new mansard roofs were permitted in a couple of conservation areas, under strict conditions.

These changes have been a real success – helping families stay in the area, providing Section 106 income for the council and sparking facade improvements which are mandated as part of the planning process. These Victorian terraces, like the one pictured below, are thriving.

New mansards in Lyal Row, E3, built after planning guidance was relaxed following a lengthy campaign.

Sadly, it’s an isolated example of a more nuanced view on mansards. And one which took an elected politician over three years, scores of meetings, petitions, consultations, the creation of several (excellent) design guides, thousands of hours of volunteer time and tens of thousands of pounds of precious planning department resources to tweak the rules for a limited part of a much broader area.

Because the rule changes do not yet apply to neighbouring conservation areas, some residents living a single street away (in near identical housing) can not build…even as they watch their neighbours extending upwards.

This means Bow now has a patchwork of different rules on mansard extensions – something which is unfair on residents who happen to live on the wrong side of a street.

All of that means the endless process of campaigning, petitioning, and lobbying the local authority is continuing, to the dismay of residents (and, one suspects, busy planners and Cllrs alike!)

Planning departments and mansards: misaligned incentives

Being part of this campaign has been a fascinating if frustrating process. Our planners are doing a difficult job with limited resources – but their jobs are made harder (and our communities made less able to adapt to today’s housing pressures) by the current framework of overly tight guidance.

Conservation area status, which impacts so many of the UK’s pre-1918 houses, adds an additional layer of complexity. In the specific case of mansards, a combination of conservation area status and the current rules have the unintended consequence of blocking a form of historically appropriate architecture which was popular with the designers of the heritage buildings which the rules are trying to protect!

In conservation areas like Bow, the fact that the introduction of mansards could be interpreted as causing “harm” to historic areas overrides almost all considerations including increasing housing density and supply, keeping families in the neighbourhood, reducing rents or improving energy efficiency.

We have learnt in Bow that planning harms can be ameliorated on a conservation area-by-conservation area basis, using design guides and Section 106 payments. But getting these things in place is really hard, as it creates a complex administrative and financial burden for LPAs and therefore a massive disincentive to action… which then needs years of concerted campaigning, political pressure and imaginative planners to overcome.

This is so unnecessary when the Victorian heritage of mansards clearly makes them a special case, with well-designed ones bringing broader benefits while remaining sympathetic (and sometimes indistinguishable) from the underlying heritage asset on which they sit.

Meanwhile, residents like us wonder how a planning system has been created where tweaking the rules on mansards takes many years (and a small army of dedicated and organised neighbours) to accomplish.

This is why we believe a stronger and more specific signal needs to be sent in the NPPF on the desirability of having mansards on appropriate pre-1918 housing, including, crucially, in conservation areas. The final version of the NPPF should be even more specific and directional on the benefits of mansards in conservation areas, and make it clear that their introduction does not constitute “harm” when designed correctly. Without it, the status quo will make any meaningful progress to densify areas like Bow – and other areas with lots of pre-1918 housing – impossible.

A presumption in favour of mansard roofs, including in conservation areas, can kickstart a wave of building and home improvement across the UK. And in doing so, it will allow residents to finish what the builders and architects of Victorian Britain started by using beautifully designed mansards to ease some of the housing challenges of today.

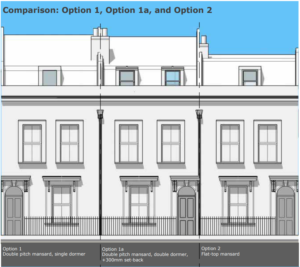

Mansard Roof Guidance, Sheet 9, Driffield Road Conservation Area

Tom Bage is a Bow resident.