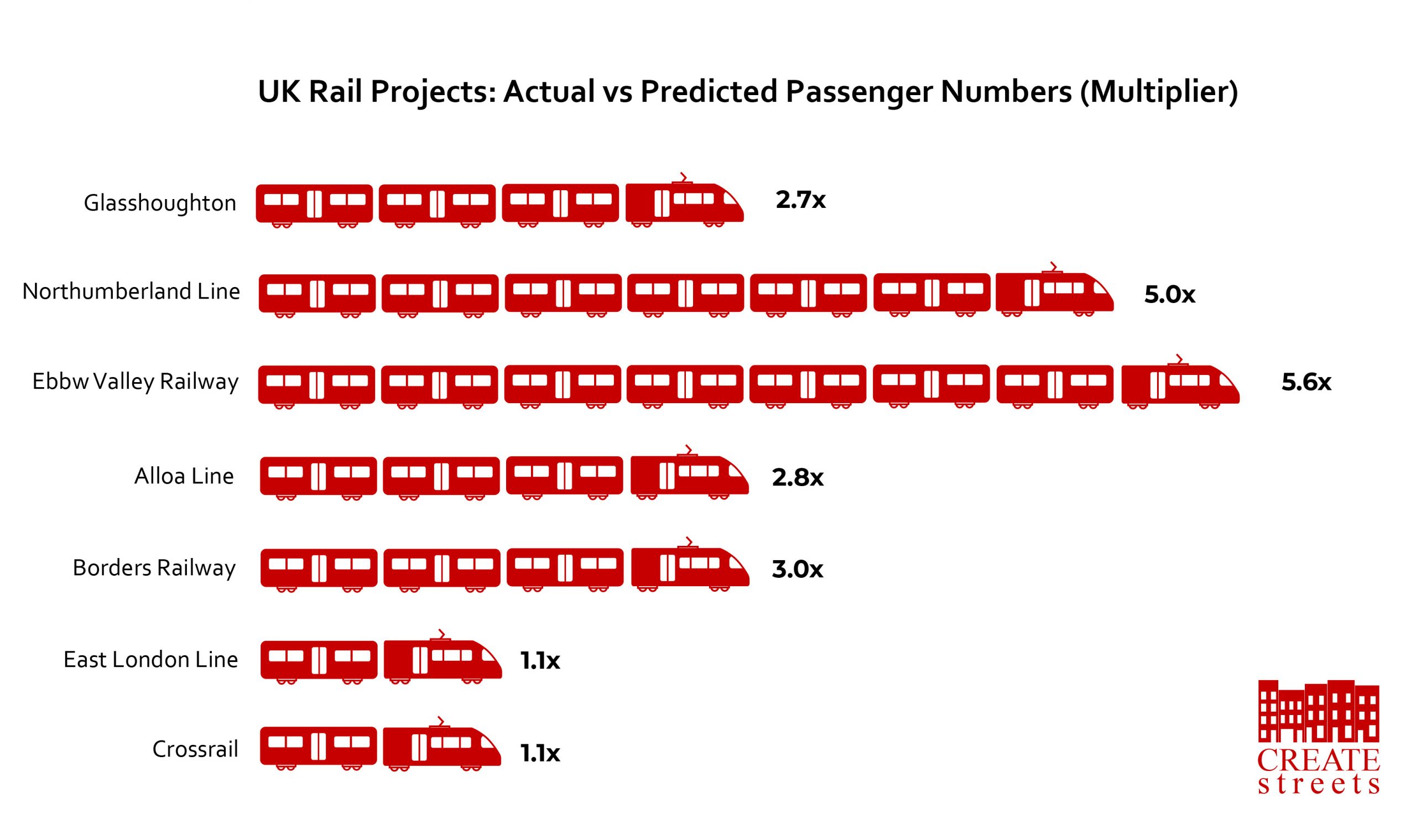

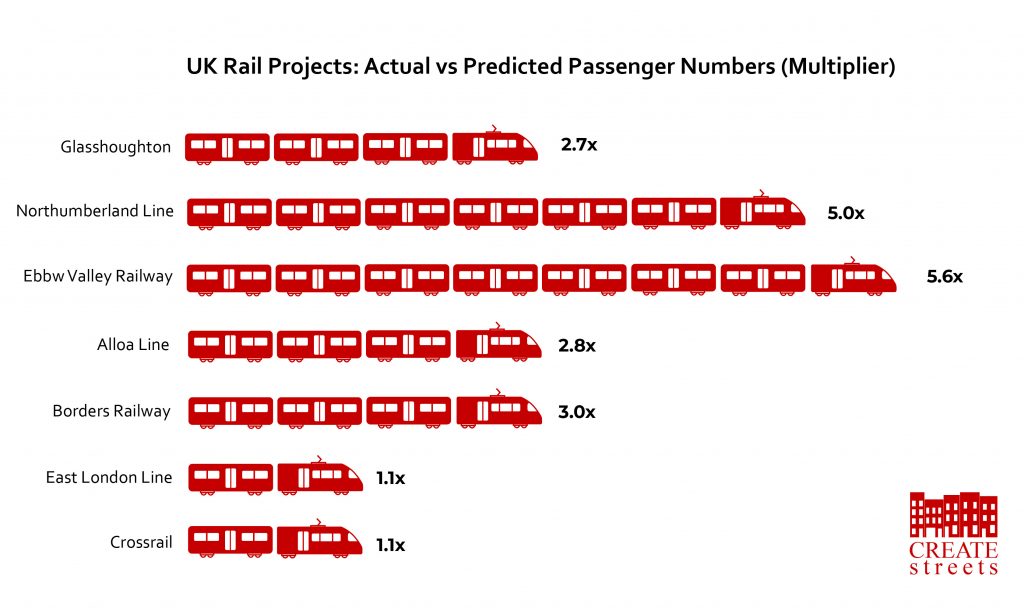

You may have recently read about the newly opened Northumberland Line, where passenger numbers have exceeded five times the predicted number. It’s easy to attribute this to some local miscalculations or perhaps an underestimation of fans heading to St James’ Park.

But this is more than just a local story. It’s a national narrative about how we invest billions of pounds in transport infrastructure and how we are missing out on ‘growth-boosting’ rail projects in towns and cities up and down the country by measuring the wrong thing, time saved not improved access.

A Closer Look at the Numbers

The Northumberland Line, at a cost of £298.5 million, was anticipated to carry around 200,000 passengers annually. However, in its first three months since opening in December 2024, the line has already seen over 250,000 journeys, putting it on track to surpass one million journeys in 2025.1

While it’s encouraging that more people are opting for the train, alleviating congestion on our roads, it’s concerning that our initial estimates were so far off. All projects undergo a Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) test to justify their existence, and the public funds allocated to them. This benefit largely hinges on the number of users and the time they save on their daily commutes.

By underestimating the numbers so significantly, this project might never have been approved. Consequently, thousands of people would continue relying on cars to reach Newcastle, exacerbating road congestion.

Innovative Funding Approaches

An intriguing aspect of the Northumberland Line project is that approximately one-quarter of its cost was covered by landowners who agreed to share the increase in their land’s value resulting from the railway’s reopening. This approach, distinct from mechanisms like Section 106 agreements or affordable housing requirements, directly ties the value created by rail infrastructure to its funding.

It’s important to note that only fixed transport modes like trains, trams, or metros can be modeled to provide this value uplift; bus stops or new roads don’t have the same effect, according to experts.

With the price of homes in Northumberland being two to three times lower than those in the Southeast, applying this funding model to a dozen new towns in the South East could reduce the reliance on public funds for transport infrastructure.

A Pattern of Underestimation

The Northumberland Line isn’t an isolated case. The Docklands Light Railway (DLR) in London, for instance, was initially conceived as a rapid bus service, then evolved into a single-carriage train, later expanded to double, and now operates three-carriage trains. In 2024, the DLR recorded 99 million passenger journeys.2

We’ve become ensnared in the belief that modeling the future is an exact science. We often end up being precisely wrong. While modeling can be useful for understanding scenarios, it should serve to achieve a desired vision, not to create one. Our obsession with a single metric, time saved, can perhaps surprisingly lead to overestimating the economic benefits of some large schemes, for example larger roundabouts, where encouraging new journeys onto the road erode the anticipated time savings.3

Measure access not time saving

Transport enables places to thrive and people to connect. Whether it’s London without the Tube, Amsterdam without bike lanes, or Venice without canals, these cities would fundamentally change in character and probably grind to a halt.

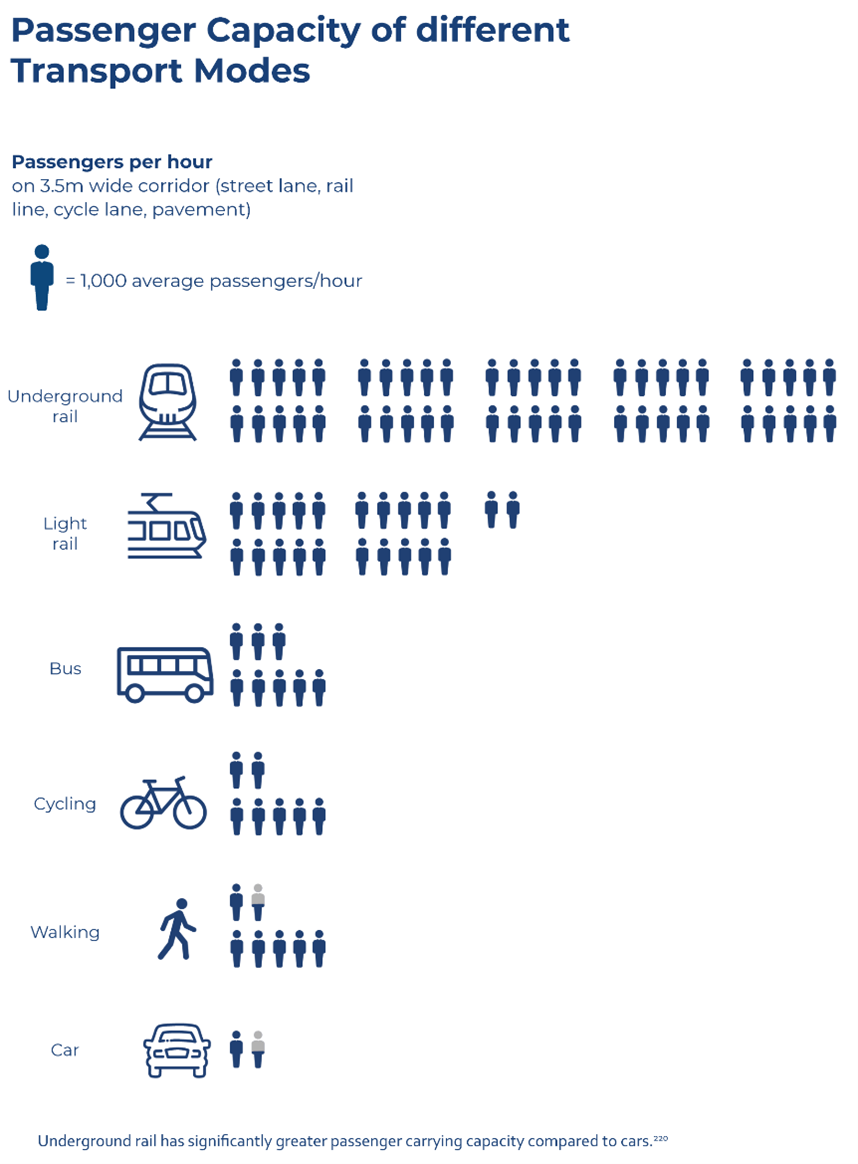

We currently focus intensely on monetising time savings benefits, which tends to favour projects that marginally optimise very busy existing routes. In contrast, many academics and transport planners advocate using ‘access’ as a better metric. This approach prioritizes schemes that provide most people with access to jobs and amenities, often through entirely new routes connecting large towns or cities.

For instance, trams and metros can have a much higher traffic capacity than cars or mixed bus and car traffic.

Focusing on access also tends to favour investing in numerous smaller local transport interventions. Examples include the transformation of Wales’ ‘Core Valley Lines’, which will continue into Cardiff as a tram, achieving metro-like frequency.

In Birmingham, successive mayors recognise that the city can’t rely solely on one form of transport. Analyst Tom Forth has revealed that Birmingham’s reliance on buses, which are susceptible to congestion, significantly reduces its effective population during peak times. While the OECD defines Birmingham’s population at approximately 1.9 million, Forth’s research indicates that, due to limited peak-time mobility, the city’s effective population drops to just 0.9 million. This diminished connectivity hampers agglomeration benefits, contributing to a notable productivity shortfall compared to similar European cities. Forth suggests that enhancing public transport infrastructure, such as expanding tram networks, could nearly double Birmingham’s effective population, thereby boosting its economic performance.4

In Wiltshire, a new initiative is gaining traction to revitalize local rail links between Chippenham, Melksham, and Trowbridge. Currently, fast trains from London limit track space to six trains per day. For a relatively modest investment of £5–10 million, a passing loop (akin to a train lay-by) could be installed, allowing local trains to run at four per hour.

Two advantages of these types of schemes are their potential for quick delivery, possibly within a political cycle, and their ability to help councils deliver new homes at higher densities. For example, Wiltshire has an annual housing target of 3,500 homes, up from 1,900 A rail-led plan could facilitate this development on 1.5 to 2 times less land, preserving valuable land for nature, farming, or energy.5

A National Perspective

There are countless projects like this up and down the country that are always the bridesmaid, but never the bride, often due to how we under-forecast rail uptake by valuing shaving seconds off a commute, instead of unlocking new, reliable routes within and between places. In many countries, any city over 150,000 would expect a comprehensive network of rail, tram, bus, and road as part of a vision to provide transport access and choice. Yet who is mentioning building a tram in Bournemouth, population of nearly 200,000, to tackle congestion and travel-to-work times?

Research from the Centre for Cities highlights that enhancing public transport connectivity in UK cities can significantly boost productivity. For instance, Manchester’s limited public transport accessibility contributes to an estimated £8.86 billion annual productivity gap, while Birmingham’s stands at £3.63 billion. By expanding and improving transport networks, these cities can increase their effective labour markets, fostering economic growth and reducing regional disparities.6

So, let’s stop missing the train and get Britain back on track by putting the metric of access, not time saving, centre stage, and give local transport the pedestal it deserves. If we do this, we might just find the economic growth we’re looking for in the cities and towns that have, for far too long, been ignored.

1 Northumberland Gazette & Rail Magazine

2 Statista

3 assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, dataportal.orr.gov.uk,eastwestrail.co.uk, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk & https://www.railmagazine.com/news/2025/03/26/nearly-one-million-journeys-projected-for-northumberland-line-in-2025?

4 Tom Forth, Birmingham is a small city

6 Cities can’t grow because of bad public transport. What’s the answer? & Centre for Cities, Measuring up