Nicholas Boys Smith suggests a little more humility in how we design and manage our streets and buildings if we want to enjoy hot summer days in the city

Nearly everything we’ve done to our towns and cities for the last century has heated them up. That might be good in the winter. But it’s definitely bad in the summer.

We’ve cut down street trees to let the cars drive faster, and to make the lives of highways officials easier. The result? We’ve lost their shading effect in the heat and we’ve lost the so-called “evapotranspiration” effect whereby the water transpiring and evaporating into the air from greenery and the soil cools us down. Streets without street trees on a hot day can be anything from 5 to 15 degrees warmer.

The ‘urban heat island’ effect is caused by this combination of sealed surfaces, dark materials and reduced greenery. It can make inner-city streets up to 8 degrees hotter than surrounding countryside. We’re turning our cities into ovens, street by street, block by block. We need to green-up our streets again.

Even worse is what we’ve done to our buildings. Come with me into a village medieval church on a boiling hot summer’s day. Pass the lynch gate and the graves in the heat and step through the porch and the heavy dark wood door. It’s immediately cooler isn’t it? Let me point out why. Look up into the rafters. The heat in the high church is rising into the roof away from your head. It’s also because the stone walls have what engineers call a high ‘exposed thermal mass.’ This means that heavy materials absorb heat during the day and then at night release the heat slow slowly helping to regulate the temperature. It’s like nature’s air-conditioning. Touch the walls and feel it. It works particularly well in temperate climates such as ours where, even in heat waves, the nights remain relatively cool.

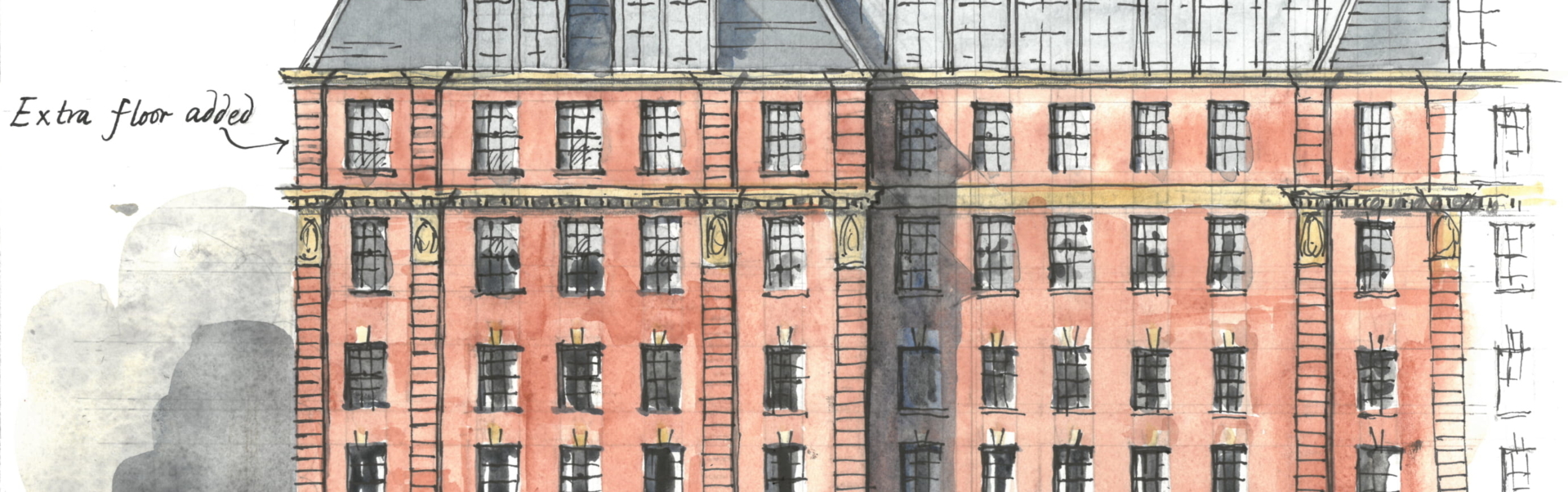

To a lesser extent the same is true of nearly all historic buildings. Imagine stepping on an old tile or stone floor in your bare feet in an old-fashioned kitchen. It’s pleasantly cool. The thick stone or brick walls, the medium sized windows which open properly, the ease with which you can open windows creating cooling currents through the building, the high ceilings (certainly in Victorian houses), all these keep older houses comfortable in hot weather. Until the early twentieth century most houses also had external shutters. These are perfect. Engineers make them sound less attractive by calling external shutters “passive ventilation” but it simply means that the external shutters keep the heat from radiating through the window. They’re far more effective than internal shutters. My parents-in-law can keep their detached French house perfectly cool in murderously hot French summers thanks to thick stone walls, old shutters and knowing precisely when to open and shut which windows at different times of the day as the sun passes overhead.

Nearly everything about how we conceive or design modern buildings ignores these traditional wisdoms. Thin skins of hidden breeze blocks or fake bricks are sliced over heavy insulation. There’s little ‘exposed thermal mass.’ These walls are good at keeping the heat in and your bills down in the winter but very good at overheating in the summer. Which is what they do. Depending on whose data you believe, overheating in Britain has increased from about 18 per cent in 2011 to somewhere between 50 to 80 per cent today. Modern building regulations are contradictory and interacting badly with planning. On the whole they are making matters worse by overcomplicating and avoiding simple old-fashioned solutions.

They make windows harder to open which stops you creating air currents. They encourage mechanical ventilation to try and design our way expensively out of the problems we’ve created. Large windows above the ground floor are now discouraged by the clumsy new Part O building regulations, unless developers pay for something called ‘dynamic thermal modelling’ to prove the home won’t overheat. In practice, this tilts the system towards expensive mechanical fixes and penalises simple traditional forms. The Part O building regulations do not even take account of external shutters unless they open and shut automatically. They are always seeking the expensive high energy solution at the cost of the simple, the cheap and the timeless.

Interestingly the new draft London Plan is starting to ‘go back to the future’ calling for high ceilings and discouraging mechanical ventilation and air-conditioning. This is ironic as air conditioning is not that dissimilar to a heat pump in reverse. Unsurprisingly, swelting Londoners are unamused. National air conditioning use has apparently increased from 3 per cent to 21 per cent and it will keep rising. Being trapped in a overly-insulated house with no external shutters and unopenable windows without the benefit of thick load-bearing walls in a heat wave is no joke.

We’ve lost the common sense and replaced it with way too much bureaucracy, expensive high energy solutions and overheated flats. What’s needed isn’t another layer of guidance or a dashboard of targets. It’s humility: to design with nature, not against it. To rediscover the lessons of centuries-old buildings that were cooler by design. High ceilings, proper shutters, generous windows you can actually open, thick walls that breathe. It’s time to learn from the past if we want more comfortable buildings in the future.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founder and chair of Create Streets