Create Streets today publishes Create Mews by our Senior Fellow, Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes and a foreword by Sir Simon Jenkins.

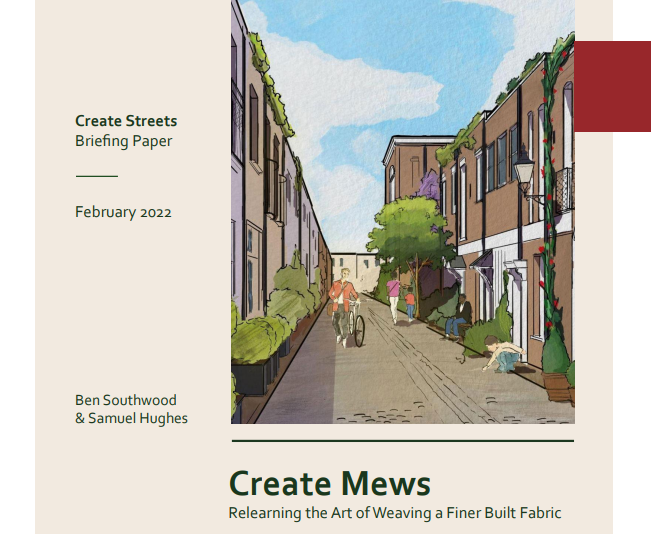

Create Mews is a major contribution to policy debate in the UK, developing the ‘street votes’ concept to create a policy tool that enables small communities to build new mews where they decide this is appropriate and desirable. Mews are inherently a walkable and sustainable typology, and are in practice often extremely beautiful, popular, and well-photographed.

The paper, which has more than 50 endorsements from major community figures, explains:

- The neighbourhood planning regime has been popular and successful in parished rural areas. There have also been successes in unparished urban areas, but uptake has not been as high. Neighbourhood forums can be too large and too hard to get designated. They do not always have all the powers they need.

- This paper suggests a way of complementing neighbourhood planning in urban areas: empowering individual blocks to set their own plans through a sub-variety of street vote. This could help to restore some of the traditional processes through which towns and cities evolved and added high-quality housing over time.

- Historically, our towns and cities expanded as much through organic intensification of existing plots as through outward expansion. Most historic British towns still feature lanes and courts built on the deep medieval ‘burgage plots’, the closes of the Edinburgh Old Town being perhaps the most celebrated example.

- Today, pressure is mounting on our skyline and our countryside, generating intense concern about inappropriate high-rise towers and loss of precious and irreplaceable green space. The time has come to revisit traditional intensification, while ensuring that we add to the greenery and biodiversity of our towns and cities.

- The recent papers Strong Suburbs by Policy Exchange and Living Tradition and Learning from History by Create Streets proposed mechanisms for improving and intensifying existing urban areas, under the leadership of local communities. These papers won broad support from architects, community groups, housing campaigners, planning lawyers, and heritage societies. The key strength is that no one would have development forced upon them, but they may band together locally to benefit from development if they wish.

- This paper builds on this previous work by suggesting a means of generating new development in the central areas of blocks, especially on the sites of disused alleyways, dilapidated sheds, waste ground and areas of rubbish dumped at the neglected ends of long yards. We illustrate this with recent projects from Create Streets, Peter Barber Architects, HTA Design, Pollard Thomas Edwards, Ben Pentreath Architects, James Wareham, Matthew Lloyd Architects and ADAM Architecture.

- Specifically, this paper proposes giving residents of blocks—that is, residents of those properties which encircle some area of land—the right to choose collectively to allow themselves to develop those spaces into new mews or other developments, so long as these are effectively invisible from the street, and compliant with extensive rules on design and safeguards for other residents. As well as helping to make better use of privately owned land, this may help councils and housing associations with the replacement of disused blocks of sheds or garages. Block residents may not use such block plans to change the facades facing surrounding streets, because other residents looking on to those facades will have had no chance to participate.

- Our most pessimistic modelling scenario finds that such block plans could deliver over 20,000 homes a year over the next fifteen years. Block plans strongly complement street plans (from Strong Suburbs), as well as the ‘mansard votes’ in Living Tradition, and the extensions suggested in Learning from History, providing many different angles from which to approach urban enhancement. These proposals will not solve every problem on their own, but we believe they are an important and helpful addition to solving problems around housing.

- Providing new homes in this way makes much better use of our existing infrastructure and is far more sustainable in its use of embodied carbon, in its infrastructure requirements and in the lifestyles and movement patterns that it facilitates. It can also enable more sustainable and less disruptive offsite modern methods of construction. It is a ‘deep green’ approach to development.

As Sir Simon Jenkins comments in his foreword:

Today’s towns and cities do not have to be demolished to house more people. It is wholly unnecessary. The greatest—and most costly—domestic policy failure in 20th-century Britain was a belief that only through replacing old towns or building new ones in the countryside could the nation expand and prosper. The popularity—and adaptability—of old streets, old houses and old neighbourhoods was of no account. Modern living required tower blocks, slabs and car-friendly ‘estates’.

I therefore see this report as a truly revolutionary manifesto, heralding the rebirth of a new British urbanism. We need only to harness the spirit of enterprise of a new generation of city residents to gain more living room. It is a revolution that may have come too late for many lost places and lost communities. But at least it has come.

Read the whole report here