By Robert Kwolek

Germany may be the land of Autobahns and Audis, but its true urban workhorse is the Straßenbahn, or ‘street train’. While Britain and North America tore up their trams after World War II, Germany kept, and modernised, theirs. Today, an unrivalled 60 cities still run trams, stitching together new housing, walkable neighbourhoods and low-car lifestyles. This essay shows how those tracks survived the mid-century cull and why they remain a cornerstone of Germany’s greener, people-first urban renaissance.

Trams criss-cross Alexanderplatz in Berlin, 1910

A brief history of German trams

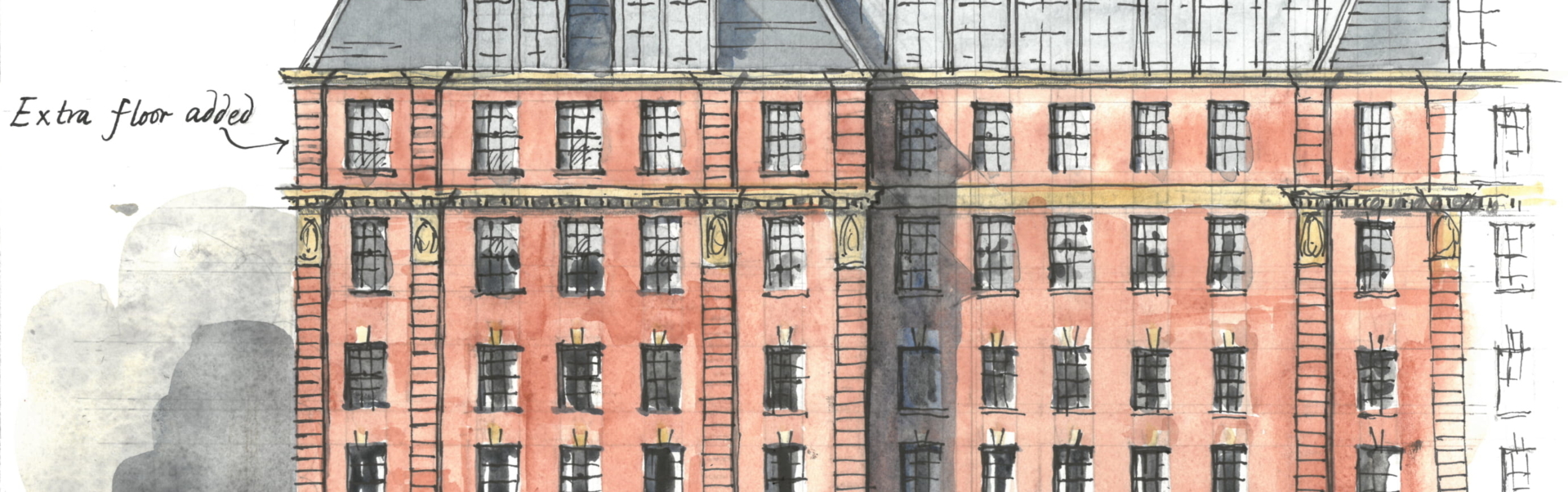

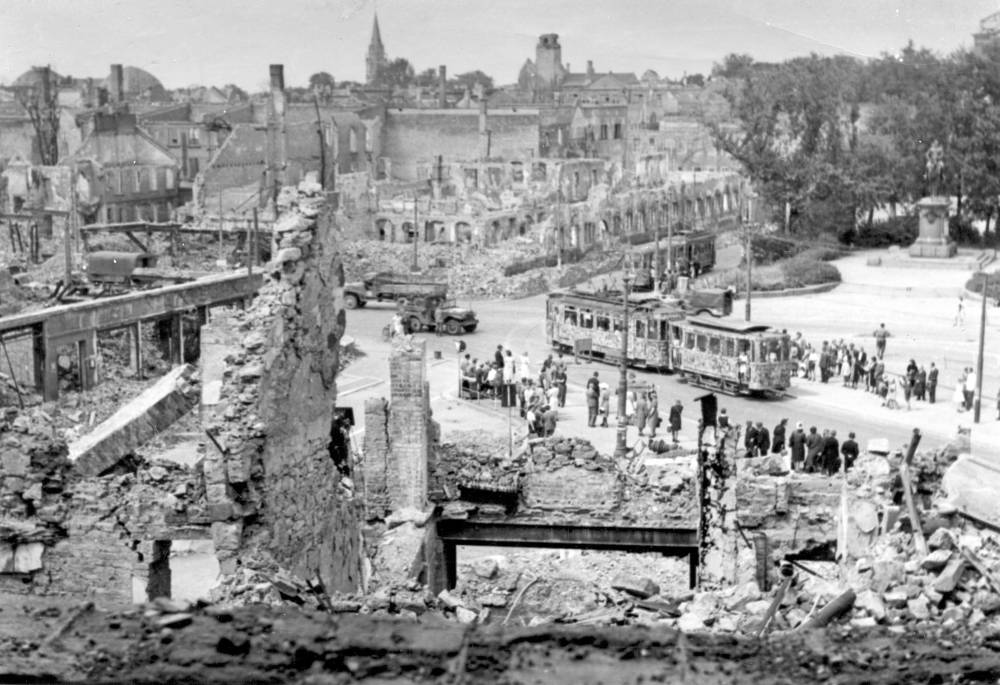

By the early 20th century, electric trams were ubiquitous in German cities, forming the backbone of urban transport. After World War II, trams (which are electric) had an advantage over buses due to fuel shortages, and many war-torn German cities rebuilt their tram lines as vital transport.

A tram travels through the devastation wrought by WWII in Darmstadt, 1945. Image source.

By the 1950s and 1960s, however, a car-centric shift was underway, especially in West Germany. Trams started to be seen as old-fashioned and some cities, like Hamburg and West Berlin, eliminated them by the late 1960s. Others, such as Munich and Nuremberg, decided to replace their trams with an U-Bahn (underground metro) instead. These plans were only partly fulfilled due to high costs and booth Munich and Nuremberg ended up retaining and later expanding portions of their tram networks. Other cities, like Hanover and Stuttgart, pursued a middle ground by putting trams in tunnels through the city centre with the intent to eventually convert them to an U-Bahn. By the 1980s, virtually all German cities abandoned these costly full-conversion schemes and trams stayed on the surface.

Berlin’s public transport operator (BVG) displayed five generations of its trams during an open depot day in 2009 – a vivid reminder of the continuity of tramway technology from the Cold War era Tatra cars to modern low-floor units. Image by Jochen Teufel CC BY-SA 3.0

In East Germany, trams were even more dominant. Socialist transport policy emphasised public transport, and funding was limited for widespread motorways. As a result, every major East German city kept its trams and many were expanded. Leipzig, Dresden, and Magdeburg extended tram routes into new Plattenbau (prefabricated apartment) quarters during the 70s and 80s. Tram networks continued to be expanded after reunification. In East Berlin a 4.5km tram line opened in 1991 through the large Hellersdorf housing estate, providing crucial links to a growing suburban district. Reunified Germany inherited a robust base of tram systems across both East and West.

Resisting a bad trend: why German cities kept their trams

Why did Germany’s trams survive when those in the UK and North America largely vanished? Several factors stand out.

- Economic realities: A postwar economic boom in the UK and US meant that car ownership skyrocketed. Car-based suburbia became the favoured built form and investment shifted to building motorways to support this new, lower density form of cities. Meanwhile, Germany was still in a deep economic depression and suffering from materials and fuel shortages. They couldn’t have shifted to cars immediately after the war even had they wanted to. Even after the formal formation of West Germany in 1949, the federal and state governments continued to provide funding for municipally owned transport companies, including trams. This public ownership structure meant that decisions about urban transport could be made locally and with long-term goals in mind.

- Policy and planning: Even as cars grew popular and Autobahns were built across West Germany, German cities remained denser, more compact, and more mixed-use and city councils were pragmatic about transport. In the 1960s, many West German cities planned to replace trams with metros or buses, but most didn’t fully follow through once costs and practicalities became clear. Unlike in the US, where privately owned and unprofitable streetcar systems were deliberately bought out and scrapped, German tram companies often remained publicly owned and focused on long-term service. By the 1970s, the oil crises also reminded Germany of the value of electric transport, helping halt further closures.

- Cultural differences: It’s difficult to understand Germany’s decision to retain trams without understanding that to German policymakers keeping trams would have seemed like the pragmatic, sensible and safe option, whereas a switch to buses would have been an unknown risky option. Furthermore, unlike in the UK and US where trams came to represent the past and the car became an important status symbol, public transport in Germany never acquired a social stigma. Trams were not associated with poverty or obsolescence, but rather with efficiency. German cities were among the first to recognize the downsides of car dependency, too: pollution, congestion, and hollowed-out city centres. Rather than widening roads and doubling down on motorways, cities such as Freiburg reinvested in trams as part of traffic calming and pedestrianisation strategies.

- Continuous modernization: Rather than letting systems decay, German operators never stopped investing in new tramcars and technology. From the 1950s, Düsseldorf based DÜWAG began supplying West German cities with modern articulated trams, and cities like Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, and Hannover introduced new, higher-capacity trams. This kept service quality high and public support strong. Trams were reimagined as a modern, attractive, clean transport, integrated into pedestrian zones and designed with attractive vehicles and stops. In contrast, many North American and British trams had been neglected and unmodernised, making buses seem like an improvement in comparison.

- The tram-train: Germany was an early adopter of the tram-train (or “Stadtbahn”) concept that mixes tram and metro elements. The best-known example is in Karlsruhe. By using dual-voltage tram vehicles, Karlsruhe linked street tramlines to existing regional rail tracks, effectively merging local and regional transport. This model has since inspired tram-trains in cities like Saarbrücken and Kassel and in Cologne and Frankfurt some tram lines go underground and now run as light-rail metros in the centre while still operating on streets in outlying areas. It’s a case where Germany led in expanding tram usage at a time when others were only starting to consider reintroducing trams.

Three further reasons were identified in a 1998 research piece by Hartmut Topp, at the time a professor and director at the Institute for Mobility and Transport at the Technical University of Kaiserslautern.

- Pragmatism: Where other countries pursued replacing trams with buses, German cities often kept trams that still served dense areas well. They chose a flexible approach which allowed for gradual upgrades rather than wholesale dismantling.

- Strong municipal operators: Many tram systems remained in the hands of publicly accountable city utilities, giving them a long-term investment outlook. This made it easier to plan for continuity and renewal.

- Public acceptance and use: Even during the car boom of the 1960s and 70s, trams were well-used. As other forms of transport became congested or expensive, trams kept their niche and their advocates.

Topp highlighted that the return on investment for trams was higher than for road-building, particularly when urban regeneration effects were included. Topp didn’t provide figures, but a 2025 study by MCube and the Technical University of Munich, commissioned by Deutsche Bahn, found that every €1 spent on local public transport generates around €3 in added economic value for Germany’s GDP.

A Tram renaissance

By the 1980s a “renaissance of the tramway” was underway in Europe. German transport experts came to see trams not as relics but as modern urban transport. High automobile traffic and environmental concerns drove many cities to enhance transport. Public opinion shifted too: trams were recognised for their zero tailpipe emissions and ability to move large numbers of people efficiently on city streets. Consequently, instead of abandoning tram lines, German cities began upgrading them – laying grassed track beds, giving trams priority at traffic signals, integrating them with feeder buses and commuter rail, sourcing new rolling stock (especially low-floor trams for accessibility) and funding line extensions. What was old was new again.

Several former West German cities that had reduced their networks started to rebuild or extend them. In the 1990s Munich, which opened its last pre-war tram line in 1948 and built a metro in the 1970s, decided to keep and grow its tram. The city has since added new tram routes (such as the Westtangente) and today enjoys strong ridership. Likewise, a newly unified Berlin began extending former East Berlin tram lines into western districts that hadn’t seen trams in decades. Multiple lines now cross the former border.

Freiburg: tram-oriented neighbourhoods

One of the clearest examples of trams guiding urban development is Freiburg im Breisgau, a mid-sized city in southwestern Germany known for its environmental leadership. Freiburg not only kept its tram network through the 20th century, it actively extended lines to serve new residential areas in recent decades. In the 1990s and 2000s, the city planned two major sustainable neighbourhoods – Rieselfeld and Vauban – explicitly around tram access.

A modern low-floor tram in Freiburg. Image by Ricard Codina, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rieselfeld, a new district in west Freiburg, received a tram line in 1997 as soon as residents began moving in, running 1.3km along the main avenue with grass track and three new stops. This line ensured residents had fast, car-free connectivity to the city centre. Similarly, Vauban – a celebrated eco-neighbourhood built on a former military base – was connected by tram in 2006. After three years of construction, the Vauban line opened at a cost of €18 million (well under budget). It added 2.5km of track linking Vauban’s 5,000 residents to Freiburg city centre. The tram was an instant cornerstone of Vauban. Most homes were built with limited parking, on the premise that the tram and cycling facilities would handle daily transport needs. Today, 70 per cent of households live without a car. Citywide, Freiburg’s tram network carries over 80 million passengers per year.

Freiburg shows how keeping and extending trams can enable tram-oriented development: new housing built along tram lines yields vibrant, low-car communities. Concrete evidence is seen in its modal split: Freiburg has achieved a citywide reduction in car usage, with only about 30 per cent of trips by car and the rest by public transport, bike, or foot, thanks in part to its tram-centric transport network.

A tram runs down the primary avenue of the Vauban eco-district in Freiburg

Karlsruhe: expanding reach with tram-trains

If Freiburg demonstrates local tram-based development, Karlsruhe provides a lesson in regional expansion of tram services. Karlsruhe famously pioneered the “Karlsruhe model” of tram-trains, allowing trams to run beyond city streets on mainline rail tracks to reach far-flung suburbs and towns. This approach enabled Karlsruhe to greatly increase public transport coverage without building expensive new tram corridors from scratch.

The breakthrough came in 1992, when a dual-system tram was first run from Karlsruhe’s city centre to the town of Bretten over an existing Deutsche Bahn railway. The result was transformative, daily ridership on that corridor jumping from 2,000 to 18,000 after service began. Commuters who once found the old infrequent trains inconvenient could now ride directly into the city on a tram, without transfers. This fourfold patronage increase exceeded all forecasts, proving the concept’s success.

Spurred by this, Karlsruhe’s transport agency (VBK/AVG) steadily expanded tram-train lines in the 1990s and 2000s. The tram network was interwoven with regional lines to create a vast integrated system. Today, Karlsruhe operates over 660km of light rail/tram-train routes, surpassing the track length of many S-Bahn systems. Outlying communities that lost passenger rail service in past decades suddenly regained rail transport into the city. Equally as important, by using existing tracks and modest street extensions, capital costs were far lower than building new U-Bahn lines or fully separate commuter rail. Karlsruhe essentially kept its trams by expanding where they could run, merging inner-city and suburban transport.

The impact on mode shift has been significant. Every corridor that received tram-train service saw a marked increase in public transport usage – meaning fewer car trips on those routes. Local officials credit the Karlsruhe model with reducing traffic growth and enabling transport-oriented growth in surrounding towns. The concept has since been emulated in Saarbrücken (which runs a tram-train to the French border) and Kassel (which launched its “RegioTram” in 2007). The tram makes it possible to live outside these cities without a car.

A tram line travels through the new district of Knielingen Nord, Karlsruhe. Image by Entbert, CC BY-SA 4.0

Leipzig: an enduring urban backbone

Leipzig, in eastern Germany, has run trams continuously since 1872, and today it operates one of the largest networks in the country, with 13 lines and 146km of track. Notably, Leipzig uses an unusual track gauge of 1458mm, the widest in Germany (a legacy of a 19th-century choice). Despite this peculiarity (which prevents sharing vehicles with other cities), Leipzig’s tram system thrived while other cities abandoned theirs.

Under East German administration, Leipzig kept expanding its tramways. In the 1970s, new lines were built to giant apartment complexes like Grünau. By 1989, Leipzig’s network was carrying hundreds of millions of riders annually. After reunification, there was some streamlining (a few duplicate lines closed), but the city quickly modernized its fleet and stops. Also, Leipzig integrated its trams with a new S-Bahn tunnel in the 2010s, complementing rather than replacing them.

Today, Leipzig’s tram network supports the city’s growth and shift towards sustainable travel. Trams carry students to the university, commuters, and new residents to housing in revitalized districts. New residential projects in the former industrial areas of Plagwitz and Lindenau are benefiting from existing tram lines that were underutilized during the economic slump of the 1990s but now see rising ridership. As a result of these efforts, public transport (led by trams) retains a high mode share in Leipzig, helping limit car usage even as the population grows. The tram network’s capacity, with high-frequency service and modern low-floor cars, is key to accommodating this urban growth.

Leipzig also illustrates how retaining trams can shape urban form. The city’s streets and public spaces evolved around tram corridors, from the grand ring road where multiple lines converge, to neighbourhood primary streets anchored by tram stops. This has encouraged more centralized, walkable development. Even new tram extensions are planned in coordination with land use. For instance, there is a proposal to extend trams into the large ‘Leipzig 416’ inner-city brownfield development to ensure it is transport-oriented from the start.

Case studies summary

| Population | Network length | Lines | Annual ridership | |

| Freiburg | 236,000 | 36km | 5 | 64 million |

| Karlsruhe | 308,000 | 504km | 17 | 70 million |

| Leipzig | 629,000 | 146km | 13 | 123 million |

Technical standards of German tramways

- BOStrab: The success of German trams owes much to clear national regulation. BOStrab (Verordnung über den Bau und Betrieb der Straßenbahnen, or “Ordinance on the Construction and Operation of Street Railways”) is the federal ordinance governing tram construction and operation. It sets out rules on track alignment, stops, signalling, vehicle design, safety, and accessibility. Critically, they are not as strict as those for regular railways. BOStrab also provides a legal framework that allows trams to share street space with cars, pedestrians and bikes in a controlled and predictable way. It enables partial segregation and priority signalling, helping trams stay fast and reliable without needing full metro-style separation. In contrast to the UK, where a lack of tram-specific standards slows planning, Germany’s national regulations make tram expansion relatively straightforward.

- Gauges: Almost all German tram systems use either standard gauge (1435 mm) or metre-gauge (1000 mm) track. The choice often dates back to historical reasons (metre gauge enabled tighter curves and avoided regulation as “railways”), but both gauges perform well for modern trams. A few exceptions exist, such as the aforementioned 1458mm in Leipzig and Braunschweig’s 1100mm gauge.

- Overhead wires: They might be considered visually intrusive by some, but German cities have long experience integrating them into the streetscape – often using slim poles or building attachments to minimize clutter. The rules around them are also regulated by BOStrab.

- Tram vehicles: Tram design in Germany has evolved in phases, but standardization has helped control costs. In the postwar years, the DÜWAG articulated tram became a de-facto standard across West Germany, meaning many cities bought similar models (often 6- or 8-axle articulated units) that could be maintained with shared expertise. In recent decades, manufacturers like Siemens, Alstom, and Bombardier have supplied 100% low-floor modular tram models for step-free boarding (e.g. the Bombardier Flexity series in Berlin and Frankfurt). Most German trams are single-ended (with a driver’s cab only at one end), because nearly all systems retained or built turning loops at the end of the line.

- Track construction: Yet another technical aspect where German practice sets a benchmark. Many tram lines run on reserved track – either in medians or alongside roads – often with grass turf between the rails (the so-called Rasengleis). This reduces noise and blends the tramway into the urban landscape. Even when trams run in mixed traffic, BOStrab regulations mandate certain safety features like signage, signals dedicated to trams, and pedestrian-friendly track bedding. The standard track gauge of 1435 mm (where used) conveniently allows interoperability in cases like Karlsruhe, where tram-trains switch onto Deutsche Bahn tracks of the same gauge. Meanwhile, metre-gauge systems have proven that even narrower trams can handle high passenger volumes. The metre-gauge tram network in Halle spans 84 km and runs 60-meter-long double trams.

In summary, German trams benefit from well-honed nationwide standardization, track gauges that suit local needs, and vehicles optimized for city environments. These technical underpinnings ensure that tram networks are robust and can easily be expanded or upgraded. They also make it easier for cities to justify keeping trams, since there is a clear framework for safe operations under BOStrab and a domestic industry capable of supplying parts and vehicles.

A tram on a grass track in Chemnitz, eastern Germany. Image by Falk2 CC BY-SA 4.0

Conclusion

The story of trams in Germany is one of remarkable resilience. When much of the world turned away from trams in the mid-20th century, German cities held on to theirs and are now reaping the benefits. Historically, this meant adapting to postwar realities and not being afraid to modernize vehicles or rights-of-way. In more recent times, it means leveraging tram networks to drive sustainable urban development: connecting new housing districts like Freiburg’s Vauban, providing seamless regional mobility as in Karlsruhe, and strengthening public transport usage in growing cities like Leipzig. German trams have restrained a shift towards car dependence by offering a reliable, high-capacity, and green alternative for everyday travel. They’ve also proven complementary to housing goals: areas well-served by trams can accommodate “gentle density” without the traffic woes that plague car-centric suburbs.

Crucially, none of these outcomes are theoretical. They are evidenced by hard facts and examples: ridership spikes where tram service is introduced, low car usage in neighbourhoods built around tram lines, and nearly 60 urban areas across Germany that continue to invest in their Straßenbahnen. As cities worldwide look to cut carbon emissions and build well-connected, liveable communities, Germany’s experience shows that trams survived not because of nostalgia, but because they worked. Trams are cost-effective, popular, and adaptable, and they help cities grow without gridlock or sprawl.

Each German city that held onto its trams has, in effect, preserved a tool for sustainable growth. And as trams continue to be runaway successes in other nearby countries, such as France, they offer valuable lessons for the UK in how to integrate transport and urban development.

A tram in Haale, Saxony-Anhalt. Image by wwwupperta, CC BY 2.0

Sources:

– Prof. Dr.-Ing. Hartmut H. Topp, “Renaissance of Trams in Germany” (1998)

– de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschichte_der_Straßenbahnfahrzeuge_in_Deutschland

– Official city transport portals for Freiburg, Karlsruhe and Leipzig

Robert Kwolek

Senior Architectural Designer, Create Streets