Nicholas Boys Smith reflets on two days in Doha.

“We are wise because we are not so highly educated as to look down upon our laws and customs.” King of Sparta as cited in Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

Last week I visited Qatar. I had been invited to chair a discussion on how public policy affects the places we create. The forum was an international jamboree called the Earthna Summit. The website was prolix. We were gathering to ‘explore how both traditional knowledge and innovation approaches can inform modern sustainability, shaping a more resilient and inclusive future.’ We were going to consider ‘hot and arid environments.’ And we were to focus on how they deploy their ‘rich cultural heritage and unique ecosystems.’

In practice this meant that rather than being within a British conversation about housebuilding, new towns and planning reform I was within a global conversation about the degradation of the countryside and despoilation of traditional towns, about the loss of local culture, craft and dignity and the ubiquitous use of imported, placeless and carbon-guzzling steel, aluminium and breeze blocks in place of locally made bricks, traditional patterns and indigenous autonomy. From everywhere I heard a cry, a plea to rediscover the local and the distinct in place of the universal and the faceless. People want to live somewhere not anywhere. They wish to belong.

It was a wide and rich conversation and one which moved me. I was particularly inspired by those nominated for the Earthna Prize for using traditional knowledge to renew their landscapes and neighbourhoods. I emerge from my visit happy and hopeful, more enthused and excited than I expected. Here is why.

The dam of heartless traffic modernism is breaking everywhere. The tide of regenerative placemaking and for relearning from traditional wisdom is worldwide and rising strongly. From all continents came stories of communities and landowners, wise planners and frustrated architects seeking to reject the worst of the twentieth century’s ugly, unsustainable and irresilient traffic modernism. We are still pouring concrete and scarring our towns and countryside with ugly and unendurable places but everywhere more people are asking ‘why?’ In Asia, Africa, the Middle East and South America more people are not rejecting the future but seeking a better marriage between traditional wisdom and modern renewal.

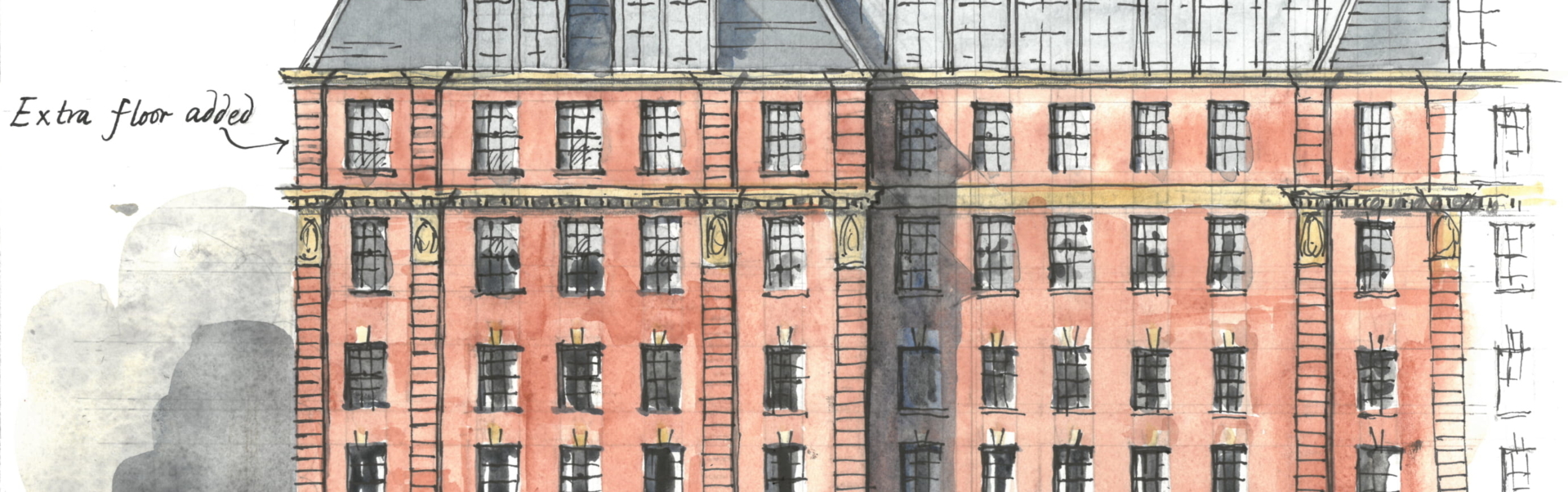

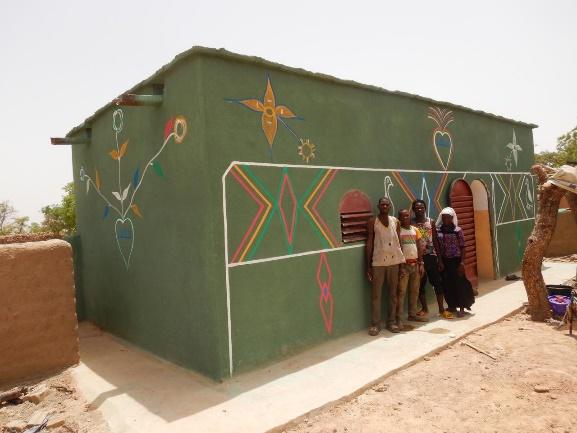

Amazing things are happening. I was touched by my conversations with the Frenchman, Thomas Granier, a grizzled and initially shy former builder who has modestly done amazing things. Working across Africa his Nubian Vault project has been reteaching and helping reseed traditional skills so that local villages can themselves create beautiful endurable homes rather than relying on contractors to take their money and pour cement. Ten thousand homes have been built so far in a growing ecosystem of change. As he said to me, ‘I want to multiply that by ten or one hundred before I die’. Hopefully, the Create Streets Foundation will also be able to support him in future.

Creating new traditional homes across Africa with the Nubian Vault

Trust the people to define place and identity. Everywhere we see a similar phenomenon. If you ask people proper questions about how people actually wish to live, you get very clear answers. People want to be more prosperous and to have more economic and health security. But they also want to belong to their own communities and cultures. They don’t wish to throw away their traditional materials and forms in the way the twentieth century thought they should. Kamil Khan Mumtaz, an important Pakistani traditional architect, told how Lahore’s residents are seeking place and identity, increasingly aspiring to a more attractive and less car-based future with more traditional streets and buildings: not returning to the past but rediscovering it within the future. As in Leeds or Lancashire, the people of Lahore care far more about living in a place than they do about obeying the zeitgeist. Membership matters more than modernity.

Materials matter. Stepping away from Britain, the debate about the use of concrete versus indigenous bricks is everywhere. Landowners and charities are commissioning reports. What are the true economic costs of concrete versus indigenous materials? What is the difference in value, flexibility and imported carbon? What is the best way to build more beautiful buildings that reflect local traditions whilst continuing to improve living standards? What buildings will last? What building techniques will re-empower local communities?

Traffic modernism is worse in hot and sandy places than it is in cool and wet ones. Heaven knows, we’ve done enough damage to our towns and landscapes. And this matters: ten of the twelve poorest neighbourhoods in England for example have dual carriageways running through them or alongside them (as shown here). But at least when we pour nitrates into our soil or rip our towns apart with wide roads and faceless buildings, we are left with a reasonably tolerant climate which does not make the consequent urban and rural landscape completely unliveable. We are not driven into bubbles of air-conditioned masonry sheltering from the unrelenting sun. But traffic modernist developments in the heat really are remarkably unpleasant: degrading into islands of air-conditioned fridges separated by motorways. It is the opposite of the civic vision of the good life. Increasingly people are realising this. They want towns in which they can belong not towns which they long to leave. This is an echo of the debate about ‘left behind’ places in the UK where for a generation public policy has inadvertently focused on helping talented people leave failing places rather than on improving the place itself.

The conversations about nature and architecture are converging. I was struck by the Dhun project near Jaipur where a programme to rediscover and recreate traditional patterns of water management and indigenous crops and agricultural techniques has brought a desert literally back to life. The inspirational leader, Manvendra Singh Shekhawat, is now planning to create a traditional new village combining historic materials and design with modern technology and street trees so that new human residents can join the birds and beasts who have already flocked back to the area. In the UK, we talk about ‘greening up’ by planting street trees and sustainable drainage. Create Streets has done much work on this and is co-ordinating community-led ‘greening up projects in places like Grimsby, Southwark and Blackpool. But Dhun is ‘greening up’ on steroids. Good.

Wise environmentalists are discovering why beauty matters. My conversation with Professor Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, whom I interviewed for an INTBAU Qatar podcast, was startling. One of the world’s most important environmental scientists, he has realised that the management and stewardship of our cities is critical for our collective futures. He is now focusing his energies on what he terms ‘regenerative architecture’, buildings whose creation absorbs carbon rather than emitting it and which are beautiful, long-lasting and resilient; tree-lined and organic not tree-less and unnatural. This is the opposite of the approach that most traffic-modernist developers and architects have taken over the last 80 years. Schellnhuber suggests that we need to ‘build with love and compassion for humans and non-humans’ creating places that are not only functional but also visually and emotionally enriching. Intellectually, from left and right, from environmentalists and from social scientists, traffic modernism is dying. The only question is: when will be able to bury it?

Learning from traditional wisdom does not mean rejecting modern innovation. This was not a conference of luddites. I had several conversations about how, traditional intelligence can ally with artificial intelligence. Perhaps surprisingly, the fear of AI and the denigration of those who deploy it that is ever present in the British modernist mainstream, appears absent from these more traditionalist conversations. Those keen to recreate human and craft-based traditional skills of design and ornament seemed to be unafraid of emerging technologies, embracing their potential to empower and expand their reach. The trick, I think, is not to confuse means with ends. Innovation and science must serve our human and communal needs, not the other way round. As Roger Scruton once wrote, ‘while a committee of experts may be suited to discussing a problem of means, it is not at all clear that it is capable of contributing to our knowledge of ends.’ Science must serve the neighbourhood and be humble enough to adapt itself to actual wants and inherited understandings of the local landscape and its idiosyncrasies. The fake omniscience of the 1940s or 1950s boffin in retrospect did enormous harm to our natural and physical worlds.

Everywhere, people are seeking purpose, meaning and dignity in the rediscovery of traditional skills. Listening to the winners and runners up of the Earthna Prize, I was struck by how consistently their work and their conception of their own programmes was framed not just in narrowly utilitarian desires to increase GDP or employment, important though that is. The prize-winners were also trying to help their villages and towns to rediscover dignity, meaning and a sense of belonging: irrigating the land, building their homes, replanting lost trees, forging a community. It felt remarkably similar to challenges of alienation and placelessness being experienced in the West as explored by Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone or my own book, Heart in the Right Street.

Doha is not so different from Darlington. Well, it’s hotter and rather richer but they both teach the same lesson about the types of places in which people wish to live. Last year I visited Darlington in Britain’s County Durham. The thriving part of the town was the historic neighbourhood which had been revived and restored and where cars, though not banned, had been relegated to second class citizens behind humans. (You can read our report, Move Free, if you want to understand why that’s a smart idea). In 2003, Doha’s historic Souk Waqif was badly burnt in a fire. Rather than just accepting the destruction, as would have been normal 40 years ago, the souk was rebuilt, with surviving old building restored and others recreated de novo. Meanwhile, post 1950 bland insertions were not restored and were actively demolished. The result is what the panjandrums of the modernist ‘zeitgeist’ view of architecture would dismiss as a ‘Disney souk’, a ‘fake’ with new buildings made to look like old. But the reality is that people love it. A thriving neighbourhood of shops and restaurants has evolved with simple and cheap material capable of infinite repair and evolution.

Meanwhile, down the road, a modern ‘take’ on traditional Middle Eastern urbanism isn’t bad. However, bereft of local patterns or ornament, it has nothing like the human interest or appeal. It relies on much more expensive materials and just does not seem to have the same ‘place attraction’. It’s vital that landowners and developers don’t forget the ‘design disconnect’ whereby most professional designers actively disagree with the general public’s preference on matters of building and street design. Most of the public need places that link more clearly to the past with more texture, coherent complexity, natural forms and sinuous curves. Most architects don’t. Wise landowners and investors must correct for this if they wish to create flourishing, neighbourly and ultimately more valuable places.

Two streets very close to each other in Doha: texture versus simplicity. It’s easier to appeal to actual people when you allow yourself the full range of historical patterns

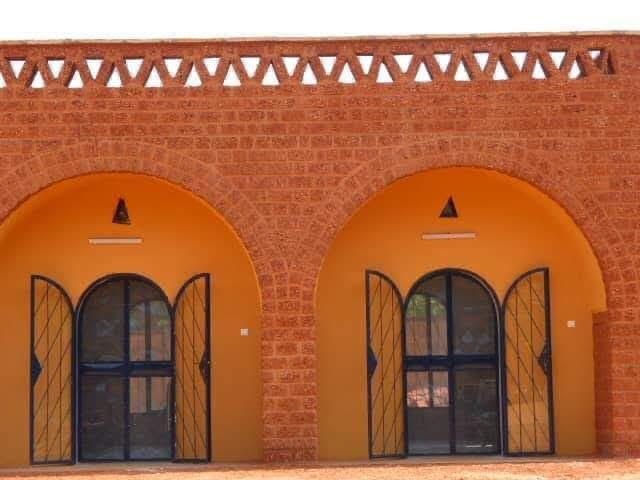

The paradox of place is that the need for home is universal but the experience of it is local. Time after time, from South America, from Europe, from African and from the Middle East I heard the same plea for rediscovering traditional wisdom in land management and in urban design. The universality of the need for place was clearest at the inspiring Heenat Salma Farm near Doha, a project led by the local charity, Caravane Earth. Here, as an exemplar project, building techniques from Pakistan and from the Qatari deserts have been combined to create simple and lovely rural buildings with high resilience and minimal embodied carbon.

From Pakistan or from Qatar? Or from both? An exemplar project at Heenat Salma Farm

* * *

Let’s not be naive. None of this is to say we don’t face huge challenges or that the juggernaut of cement and dual carriageway is not still hurtling onwards. The wisdom of the old is being lost everywhere. But there is hope. Across Europe and Africa, Asia and the Middle East, brave and wise individuals, increasingly backed by rich ones, are seeking a better way to create and manage places, and a future that does not reject technology but marries it to traditional wisdom, local beauty and human flourishing. Amen to that.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founder and chairman of Create Streets.