Here is an excerpt from More Good Homes written by Create Streets founder Nicholas Boys Smith in partnership with the Legatum Institute.

‘The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun’

Ecclesiastes 1.9

Far too many political commentators assume that state intervention in land use decisions ‘started’ with the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, and is mainly about the green belt preventing urban expansion. Historians of ‘planning’ cast their line a little further out and normally tell a tale of government starting to intervene in town ‘planning’ during the nineteenth century in response to the appalling and increasingly polluted and insanitary conditions of growing Victorian industrial towns clogged up by soot and smog—as well as the pressure for change from below that this created. They are both wrong or, at best, recklessly incomplete perspectives.

For as long as there has been government, it has sought to minimise disputes between its people. And buildings and property are amongst the most consistently contentious issues, particularly with the risk of fire spreading from one building to another. Government intervention in urban land use decisions is therefore as old as cities. The Romans did it. And there is evidence of English governments doing it probably in Anglo-Saxon towns and very certainly in medieval and early modern towns. This profoundly changes the question from should government regulate land use and urban form to how do we do so as efficiently and effectively as possible.

What actually happened in response to growing cities, overcrowding, pollution and political agitation in Victorian and Edwardian Britain was categorically not the creation of state-influence over development decisions. That was age old. However, it was extended and the idea and then the practice developed that the state should directly finance housing for the poor. Finally, in 1947 and almost uniquely in the West, Britain moved away from regulating what could be built (i.e. setting clear rules for what could be built) to nationalising development rights (i.e. vesting in the state the right to develop and only granting it to individuals on a case by case basis). This was a system that had (in a very different and more corrupt fashion) been attempted, and then abandoned, in and near London in the early seventeenth century. Other countries, with both common law and more European legal systems, take what is often referred to as a more ‘zoning’ approach where what is permissible is more predictable with fewer discretionary powers.

It is worth briefly setting out the long history of British ‘planning’ and building regulations and some of its drivers to make the point.

Building regulations in ancient and medieval England (100AD to 1580)

Under Roman rule, British towns generally appear to have been subject to the same laws and practices as the rest of the Empire. Roman regulations generally consisted of detailed specifications, including details of building procedures, how stones were to be laid and wall thickness. There is also evidence of land use regulation in Anglo-Saxon England, with rectilinear planning of sites and apparent regulation of distances between buildings in towns such as Winchester, Hereford and pre-conquest Canterbury. Later new towns such as Stratford-uponAvon and New Sarum (Salisbury) were clearly ‘planned’ with the setting out of street grids and specific plots for shops and houses. Most other new towns, however, were not planned in detail, though their boundaries were clearly set. Medieval England was astonishingly ambitious in the creation of new towns: ‘particularly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, landowners were founding towns all over England.’ 60 new towns (or boroughs) were created in Devon alone. In most cases however:

‘most landlords…made no attempt to lay out their new towns. They gave them charters, sometimes supplied building materials, offered low rents and other inducements, but they were content to let the town grow—if it were to grow—as it liked within the prescribed area. And when that area was satisfactorily filled, they were prepared to extend the boundaries of the borough by granting more land for building.’

Building regulation, rather than spatial planning, does, however, seem to have been quite common. The first extant regulation is from London in 1189. Henry FitzElwyne’s Assize of Buildings granted individuals the right to have construction halted until the Mayor could rule on a dispute. It included regulations with specific numerical requirements, such as:

‘When two neighbours shall have agreed to build between themselves a wall of stone, each shall give a foot and a half of land, and so they shall construct, at their joint cost, a stone wall three feet thick and sixteen feet in height’.

In 1212 thatched rooves were banned in London and old buildings obliged to re-roof themselves with ‘tiles shingles, boards or…lead’ under pain of being pulled down. Regulations of 1276 and 1466 set the minimum ground floor storey heights when adjacent to a street. Many legal disputes in medieval England involved argument over whether different landowners were (or were not) in contravention of specific rules (or common law custom) about what they could or could not build. In 1302, Thomas Bat was ‘hailed before the Mayor on a charge of neglecting to put tiles instead of thatch on his houses.’ And, in a surviving late fourteenth century legal case, the plaintiffs argued that a chimney should have been built of ‘plaster and stone, as the custom of the City requires.’

Other towns and cities adopted comparable building controls to maintain the streets or prevent fire though it is not clear how many, as records are very incomplete. Bristol banned houses that encroached into the street by the late fourteenth century. Salisbury banned thatched rooves in 1431. And in 1467 Worcester banned both thatch and timber chimneys.

Nor were constraints on a landowner’s rights constrained to towns and cities. The tradition of common land and of the age-old rights of peasants to pasture animals on open fields were powerful and, according to the seminal history of the English countryside, ‘jealously safeguarded and preserved.’ Certainly, the Tudor state actively intervened to prevent the ‘enclosure’ of common land. Landowners were forced to pull down hedges and restore lands to common use. Licences were required in law to enclose land.

Planning 1.0: London’s Elizabethan green belt and the first attempt to nationalise development rights (1580 to 1666)

Though it may seem surprising, late sixteenth and seventeenth century London had a green belt and attempted to regulate building in a comparable way to modern Britain. The London of Elizabeth I and James I, of Globe and gunpowder plot, of Civil War, Cromwell and Commonwealth may have had little in common with the modern city. However, like today’s capital, it was not allowed to grow.

The late Tudor city was growing. The response was not to let it but to try to stop it. From 1580 until 1661, City of London authorities attempted not just to regulate what was built but also where it was built. Under pressure from London’s Mayor and Alderman, four successive monarchs and the Parliamentary Commonwealth all attempted to prevent building beyond the city limits. At least three Acts of Parliament, nine Royal Proclamations and innumerable Orders in Star Chamber and letters to and from the Privy Council attempted to ban the construction of new building within one, two, three or five miles of the City Gates and of Westminster (details changed over time), other than on existing foundations. From 1608, no new building or rebuilding was possible without a licence under pain of imprisonment and demolition. As one historian put it, ‘modern planning regulations seem puny by comparison.’ Under Cromwell, any new home built within ten miles of London required four acres of land with it.

These attempts to prevent the city’s growth were certainly not fully effective. But it was not for want of trying. The Courts of Alderman and of the Star Chamber seem to have been active in prosecuting illegal building. Many illegal new buildings were certainly pulled down. And in 1615 a commission was established to monitor new buildings and prevent construction within the prescribed zone. Over time, the ban seems to have evolved into a modestly more controlled system where government demanded returns of new houses to be submitted and where some building was permitted under licence and on payment of a fine. In short, around London at least, the state was not just regulating what could be build, but had nationalised a landowner’s right to build. (Landowners could not build without caseby-case permission).

Motivations for this Elizabethan green belt were complex. They certainly included the City authorities’ desire to maintain control, but also a dislike of immigrants to the city, a desire for ‘the preservacon of the healthe of the Cittie’ and a dislike of ‘the desire of Profitte’ of ‘covertous Buylders.’ If these motivations seem very familiar in the modern debate about housing so do some of the consequences. Fearful that new buildings might be pulled down, development seems to have been of lower quality. The historian of the growth of Stuart London and its regulations concluded:

‘The various restrictions on building tended to produce the very evils they were presumably intended to prevent or cure. Only the cheapest houses were erected as there was a risk of their

being pulled down for a breach of the building rules, and these were put as far as possible out of the way…Another result was cheap additions with big cellars underneath.’

Big cellars in London due to high prices and regulation: history never quite repeats itself, but it can rhyme. One of London’s great seventeenth century developers, Nicholas Barbon, also concluded that building restrictions had encouraged emigration to the new world. Perhaps America owes some of its origins to the Elizabethan and early Stuart green belt?

Some other cities witnessed similar concerns at uncontrolled expansion. However, we have not been able to find evidence of any other fully-fledged Tudor or Stuart green belts. For example, in 1606 the University of Oxford attempted to secure an Act of Parliament to remove recently built cottages. They did not succeed although some cottages were demolished. In the eighteenth century the freemen of Nottingham were more successful in using historic common land to block their town’s extension—a sort of common land green belt. The consequences were high prices, overcrowding and ‘some of the worst slums of any town in England.’ Sometimes glebe land could have similar consequences of preventing development. Under Acts of 1571 and 1572, glebe land could only be let for a maximum of forty years. This dissuaded builders from taking on these plots.

Throughout the Elizabethan and early Stuart period, the need to control what could be built so as to attempt to manage fire risk and sanitation continued even if, in London, it was overshadowed by the attempt to constrain the city’s growth. For example, Charles II’s 1625 proclamation did not just demand no building within three miles of London. It also reissued regulations for brickwork in walls and window frames, for wall thickness, against jetties and on standardising brick making.

It is hard to be conclusive about building regulations elsewhere. However, they seem to have been less comprehensive than those in London—perhaps not surprising given the high cost, for example, of a private Act of Parliament. But they certainly continued to exist. Calais (under the English crown until 1558) had a 1548 Paving Act, which banned the use of thatch and insisted on slate or tiles for rooves. And there were certainly very many other local rules or practices which (as in the Middle Ages) continued to do likewise. For example, from the early sixteenth century, Oxford city and university authorities made by-laws and stipulations in leases discouraging thatch or chimneys not made of brick or stone.

After the Great Fire: abandoning Planning 1.0 and moving from a ‘green belt-first’ policy back to a ‘buildings-first’ policy in Georgian London (1667 to 1830)

After the 1666 Great Fire of London, there was a sea change. The authorities abandoned their attempt to constrain growth and focused instead on quality control. As the principal historian of London’s seventeenth century growth concluded, ‘the general attitude of the authorities towards building had manifestly changed, and regulation rather than prohibition was more general.’

The crucial step was the 1667 Rebuilding of London Act. This remarkable piece of legislation brought together, systematised and improved on at least four hundred years of edicts, City regulation and common law. It did not control the right to build. However, it did constrain what could be built. It dictated not just material (brick and tiles) but also set the height and types of buildings based on the width and nature of the road. The Act also determined the development of façade design and decoration by setting only four types of building that could be built and where they could be built: ‘fronting by-streets and lanes…fronting streets and lanes of note and the Thames…fronting high and principal streets… [and for] persons of extra-ordinary quality not fronting either of the three former ways.’ Storey heights, wall width and number of storeys were all set. Surveyors were appointed to ensure that the rules were followed. Crucially, the Act contained no prohibition on building beyond London. A few further attempts were made to constrain building beyond the City boundaries (for example in 1671, 1677 and 1709) but they could not win Parliamentary support. The desire for exemptions and support for the quality of the extended city being built was too strong.

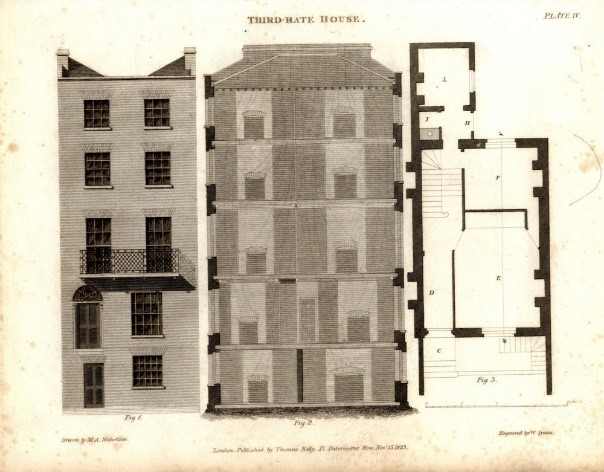

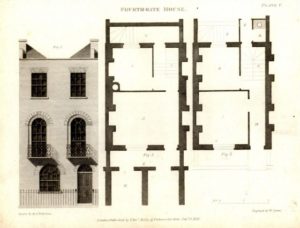

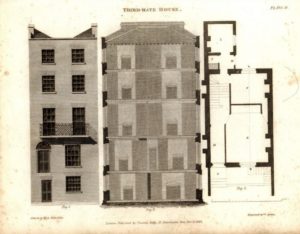

The 1667 Act arguably set the direction of building regulations for the next 250 years. It only applied to the City of London. However, a further series of London Building Acts extended that to Westminster (in 1707 and 1709) and then to the entire now rapidly growing city (in 1774). These Acts also enhanced protection against fire with increasingly strict rules against exposed timbers in box sashes and introduced rules on bow windows, shop windows and doorways. In turn, a series of builders and developers published standard plans for houses that were compliant with legislation. To look at them now is to look at London. And they are very easily dated as they adapted to evolving legislation. Most houses in London for nearly 200 years were built to fairly standard patterns taken straight from books. The Georgian and Victorian city looks like it does not just due to ‘fashion’ but because statute said what it could look like.

Third and fourth rate houses from Peter Nicholson, The New & Improved Practical Builder (1823)

London landowners were keen to take advantage of the legislation by laying out patterns of blocks, streets and squares, which did not just meet but went beyond the statutory minimums. Without deep debt and credit markets, rather than develop homes themselves, landowners leased out smaller or greater numbers of homes to smaller builders and developers. They typically insisted on similar facade and materials via covenants and contract which also directly invoked the Building Acts. This worked well for the estates in west London that were able to attract richer tenants. It worked less well in south and east London. In short, where they could, developing London landowners were extending the environmental control made possible by law.

Town planning and building regulation in other cities (1667 to 1830)

This pattern of quite strict building control to prevent fire and maintain elegance spread increasingly, though imperfectly, across the kingdom. Where it did not, as in London, developing landowners could be very willing to meet the deficit by setting down what could and could not be built by covenant as they leased plots to individual builders.

Similarly, after 1660 the government ceased opposing the enclosure by private landlords of historic common land as it had been doing since the 1520s. This had far-reaching consequences for land use patterns and farming practices:

‘[The government’s] efforts had, it is true, been largely ineffectual, but down to 1640 they had acted as a break on wholesale agrarian change. The new government of landlords at the Restoration was of a different mind, and all over open-field England parishes were transformed from a medieval to a modern landscape.’

In towns conflagration was often the primary catalyst for legislation. For example, the 1694 Act for the Rebuilding of the town of Warwick followed a fire two months earlier and did not just permit street widening. It also set precise building rules for what could and could not be built, particularly on public facades.

‘Houses were to be of brick or stone and roofed with tile or slate; two stories were to be the general rule, though three could be allowed, and the height of each was specified. Party walls were to be of uniform thickness, brickwork between adjoining houses was to be bonded together so that no straight joints would appear, timber framing and thatch were forbidden.’

As in London, the commissioners appear to have been fairly rigorous in insisting upon the regulations with, for example, some owners being forced to dismantle dormer windows that did not comply. Rear elevations, by contrast, were much less regulated.

Similarly, in Edinburgh after a series of fires, an Act of the City Council in 1674 gave the Guild Court the authority to enforce new building regulations and restricted buildings to five storeys. This was ratified by an Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1698. Further building controls were introduced in 1767 with stricter ones in 1782 and 1785. Bristol passed Building Acts starting from 1778. One historian has concluded that ‘by the 18th century some kind of building control had been established in many British cities.’

Of course, there were many important nuances and variety. Most towns do not seem to have been covered by Parliamentary Statute. However, there were local stipulations and ground landlords increasingly (though not always) used strict covenants to control what was built. The Corporation of Liverpool, for example, considered every application for a granting of land from the 1740s onwards. There was much negotiation on the width of roads. From the 1780s and 1790s, the Corporation began proactively setting out the layout of parts of its estates. At the same time, the Corporation took more of an interest in the buildings. It appointed a General Surveyor in 1786. He was expected to ‘set out the buildings according to the exact dimensions expressed in the lease’, and to inspect the designs, ensuring they were compliant. These varied, and could include both specifications about the building itself but also requirements to carry out work on local infrastructure, such as the provision of sewers or paving.

The Corporation began requiring bonds from lessees to ensure compliance. They also sometimes insisted that houses were built according to sketches drawn by the Corporation or according to ‘fixed elevations’. However, in other backstreets, there were fewer constraints. Elsewhere (for example the Brunswick Square Act of 1830) legislation sometimes helped with the enforcement of covenants, which intended to maintain urban and building quality.

However, eighteenth and early nineteenth century development was a little less laissez faire than this might imply. Set against this relative freedom of the landowner with respect to the state, it is crucial to understand that landowners were very often constrained by legal arrangements historically preventing the sale or division of a property. Entails often constrained the inheritance of estates to certain heirs over many generations. (Think of Mr Bennet not being about to leave his Longbourne estate to any of his five daughters in Jane Austen’s Pride in Prejudice). To ‘break the entail’ landowners used Parliament to secure ‘Private Acts.’ This resulted in many acts being passed (over 700 between 1800 and 1850) and the practice continued up to 1882, when the Settled Land Act gave landowners greater freedom. However, this was expensive, costing around £150-£300. For larger developments this was affordable. For smaller properties, the cost of such a bill could be prohibitive, often delaying development for decades.’

Increasingly throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, town and city corporations also made use of private acts of parliament to permit strategic improvements to their cities, normally by permitting compulsory purchase to allow the creation of new streets (often linked to new bridges) or to widen existing ones. Frome, Bristol, Shrewsbury, Worcester, Taunton, Newcastle, Liverpool, Bath, Brighton and Huddersfield were among the many examples.

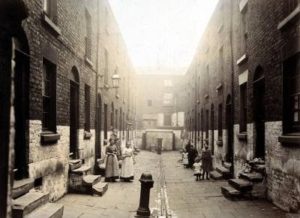

Victorian towns and cities: from local to national building regulations and building the ‘byelaw terraces’ (1830 to 1900)

Despite the spread of Building Acts and local acts, building regulation was still a patchwork by the early nineteenth century, with a mixture of legislation, covenant and common practice very imperfectly controlling the quality of what was built, and (crucially) the living conditions of those housed in what already existed. There can be no doubt that for the poor and the working classes, the living conditions permitted by the amalgam of societal wealth, housing, health and Poor Law administration remained ‘pitifully inadequate’—as London’s 1830s Commissions of Enquiry were to reveal. As the industrial revolution created mass urban employment in mills and docks, a rapidly growing population came to live in towns. They needed to be able to walk to work every day. By 1851, more than half the country lived in increasingly large and polluted towns and cities—many of them in homes built beyond the boundaries of existing building regulations or away from the eyes of their over-stretched supervisors. Many were in so-called courts, built on the gardens and backyards of existing houses and often approached by an archway penetrating the parent house.

Conditions were not always as bad as this. Some historians have judged that the houses occupied by working class families in these rapidly growing cities, ‘were probably no worse, taken individually, than the country dwellings they had originally inhabited.’ However, what certainly had changed was the sheer scale of towns with all the concomitant consequences: ‘as long as each house was detached, refuse, liquid and solid could easily be disposed of….But now the density and sheer size of the new working class districts made refuse disposal almost impossible: open sewers ran along the roads, every available corner was piled high with rubbish.’

Insanitary conditions and frequent over-crowding led not just to misery, but also to cholera. Epidemics in 1831, 1848-9 and 1866 fuelled growing and well-justified concern about the living conditions of the urban poor. A consequent attempt in 1841 to create national building regulations failed. But the 1844 London Building Act extended the 1774 London Building Act to a much wider area (to reflect the growth of London) and introduced new rules intended to improve houses and public health. In addition to updated rules on materials, storey height and wall thickness, minimum-sized backyards were stipulated, alleys were given a minimum width of 20 feet and streets a minimum width either of 40 feet or the highest building in the street—whichever was greater. For the first time builders were required to give the district surveyor two days’ notice if they were to construct a new building or alter an existing one. Over the next 14 years, the spirit behind these rules was extended nationwide. First of all, the 1848 the Public Health Act gave Local Boards of Health the clear right to create byelaws covering building regulations. Then the 1858 Public Health Act suggested more details: minimum street widths of 36 feet, 150 square feet required behind each house and a minimum distance between buildings at the back of 10 feet or 15 feet for two storey buildings. Nearly all major towns issued byelaws according to these two Acts within the decade. The 1875 Public Health Act further required running water and an internal drainage system in all new homes. And in 1877, the government issued model byelaws (based on the 1875 Act) suggesting more details.

The Public Health Acts probably stand second only to the 1667 Rebuilding of London Act as a seminal point in the history of the regulation of British building standards. By the mid-1880s, nearly all municipalities had issued byelaws. Finally, in 1901 Model Byelaws for Rural Areas were introduced. There is very wide evidence that these laws were strictly enforced. In fact, with less scope for variety than in post 1947 Planning, if anything the rules on urban form were more strictly enforced than in modern Britain. Therefore, just as Georgian London is physically readable from the four London Acts from 1667 to 1774, most late nineteenth century ‘byelaw’ streets or ‘byelaw houses’ are very predictable from local legislation. They tend to have long streets of two storey terraces punctuated by cross-streets and ‘long back alleys usually only a few feet wide running between the high walls of little yards, the latter each stretching about 10 to 15 feet back from their respective houses.’ Nearly all are two storeys high without a basement. Differences from town to town in bay width, material or street widths were a matter of variety in local byelaws as well as local economics and available materials.

London remained governed by the (slightly different) 1844 London Building Act and then the 1894 Act and so was built to a rather different pattern. Many of these terraces (particularly in northern cities, which saw heavy depopulation from the 1930s, often for 60 years) have been demolished but, unlike the court housing they superseded, they were not slums. The great historian of the English terraced house, Stefan Muthesius, lamented in 1982;

‘The mistake made by so many housing reformers of this century was to fail to distinguish between the bad conditions of the crowded dwellings of the earlier nineteenth century, and the better dwellings of the later years. In the case of the later houses it was chiefly an aesthetic dislike of the housing reformers.’

In fact, at the time, mid to late nineteenth century British building regulations were widely admired abroad as ‘brief, flexible, lenient, but strict and detailed where it had to be.’ In case all this sounds like an ‘inevitable’ road to the modern British planning system, it is worth re-stressing that it remained radically different to the post-1947 system. Although increasingly stringent and broadly expected building quality standards were insisted upon, surveyors had no right to refuse developments that met the rules. Building was regulated. But, compliantly conducted, it remained the property owner’s right to build. The 1667 Rebuilding of London Act had, conceptually, spread nationwide.

Homes for heroes, council houses and English zoning (1900 to 1939)

Of course, many residents of Britain’s towns and cities remained not just desperately poor but reliant on awful and overcrowded housing in teeming and filthy cities. Often this was older, once elegant housing, now abandoned by original tenants and crammed by tenants and sub-tenants desperately trying to make ends meet. Classic examples included the elegant terraces of London’s Spitalfields. Built for early eighteenth century Huguenots, by the early twentieth they were crammed with London’s poor including many Jews who had fled the pogroms of Tsarist Russia. The smog and filth of a coal-powered economy did everything it could to make this worse. This led to growing pressure ‘from below’ for change.

One response to the desperate squalor and over-crowding of the urban poor was for the state to build homes themselves. There was an ancient tradition of charitable delivery of homes for the old and impoverished. Why not local government? The first ‘council houses’ were built in Liverpool under an 1864 Act. More were built in Glasgow a few years later. However, these were the result of city-specific Acts and local initiative. The Housing and Town Planning Act 1909 gave local authorities the power to prepare schemes of new housing. The Town Planning Act 1919, promulgated in the shadow of World War I and with a determination to build ‘Homes for Heroes’, made the preparation of such schemes obligatory on Boroughs or Urban Districts with a population of more than 20,000. Local Government started to do so and had built many thousands by World War II.

A second response was to abandon the historic filthy cities and start again in lower density ‘garden’ developments. And the invention first of the train and then the motor car made this much easier to do. Work and accessible income, no longer had to be within walking distance. Human settlements could, so to speak, spread their wings. This approach was initially utopian, often socialist, dreaming of new and better settlements untainted by the grim grime of the present. The mill owner and philanthropist, Robert Owen, conceived of an ‘ideal village’ and tried to found one, New Harmony, in the United States. It came to nothing. Other thinkers attempted various new model cities along communal or radically alternative lines. Most petered out into normality as the pressures of economics or individual desires asserted themselves. More successful were the workers’ villages, picturesque and green, built by philanthropic industrialists away from the filth of Victorian cities. Saltaire (from 1853), Bourneville (from 1878) and Port Sunlight (from 1887) were the best known and most influential. In Bourneville, for example, homes were built at eight to the acre and were surrounded by parks and fruit trees. These were no longer cities but suburbs. But how much better they seemed. One visiting journalist reported that he was ‘charmed with the place…I felt how different is the lot of these Cadbury girls compared with many thousands of their enslaved and sweated sisters dragging on a jaded and hopeless existence in our large manufacturing towns and cities.’

Surely, this should be the future not the coal-smeared Victorian city? And these suburban planned developments encouraged a growing belief that the historic city was outmoded and a confidence that new developments could be designed by philanthropic top-down planners not an amalgam of landowners and builders. There was ‘nothing gained by overcrowding.’

Visionaries, such as Ebenezer Howard and Raymond Unwin, as well as the practical work of organisations such as the National Housing Reform Council, helped ensure that the garden city model was to become not just possible but obligatory: ‘rather than renewing urban life [they]…would fatally undermine it.’

The Town Planning Act 1919 responded to both themes of more council housing and a suburban development model. It did not just oblige council ‘Homes for Heroes.’ It also responded to the growing desire for space and air. The Act demanded much more generous space standards as set out in the 1918 Tudor Walters Report—standards that could only really be met on virgin land: terraces of no more than eight houses (which often led to culs-de-sac) and a density of twelve homes per acre.

With associated rapid developments in mass transport, thus began the building of municipal housing estates on town peripheries—‘the basic social products of the twentieth century’ as Asa Briggs described them. Ironically given the Act’s focus on ‘town planning’, the state’s regulation of construction had, critically, moved from being accepting of urbanity to demanding of suburbanity.

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 introduced the concept of ‘Planning Permission’ into British legal history. It also extended the powers of local authorities to approve buildings from the towns and cities (where the Public Health Acts had applied) to almost any type of land if there was an approved plan in place. The contemporary view was certainly that it ‘considerably extended the powers of local authorities in relation to planning schemes.’ However, and crucially, it was much less ambitious for the new ‘Planning Permission’ than the old Public Health Acts as it focused more on use than on detailed form. The Tudor Walters standards were arguably more important in defining what could be built:

‘The scheme was in fact a zoning plan: land was zoned for particular uses— residential, industrial and so on. Though provisions could be made for limiting the number of buildings, the space around them. In fact so long as the developer did not try to introduce a nonconforming use he was fairly safe.’

By 1937 about half the country was covered by draft planning schemes. But these plans, even at Tudor Walters densities, were not stemming the potential for new homes for the increasingly prosperous and growing population. The plans held sufficient land zoned for housing; it has been calculated, to accommodate 350 million people.

Planning 2.0: socialism and common law—the British experiment (1947-today)

Recent historians of ‘planning’ have presented its rise as a victory of state involvement over ‘laissez faire sprawl.’ But it is not as simple as that. Suburbs were the creation of many phenomena, mental, economic and technological; the garden city movement, faster transport, a richer society, the natural human desire for space and the new space standards, which all but banned new urban development.

An average 300,000 houses were built every year in the 1920s and 1930s, funded partly by the state, building for heroes in the wake of World War I and then by private developers as mortgage finance became widely available. Four million houses were built and the measurable standard of living of the British people was unquestionable improved.

However, there was a consequence. All these homes needed land. And the much lower density buildings standards from 1918 demanded far more of it than ever before. This led to growing criticism and resistance both from within elite groups but also far beyond. The quintessential English countryside was at risk. Who would save it? The Council for the Protection of Rural England was founded in 1926—with a leading role being played by planners such as Patrick Abercrombie. Buttressed by widespread and growing popular and political support, it quite rapidly achieved its first legislative victory. The Restriction of Ribbon Development Act 1935 permitted Highway Authorities to prevent building within 220 feet of roadsides. Highway Authorities quickly learnt to flex their new muscles and ‘ribbon development…was a largely forgotten problem by the onset of the Second World War.’

Which was more important? Adequate space for homes or protecting the countryside? Different aims of the emerging planning movement were thus in tension with each other. How could they be resolved?

As is well known, the experience of World War II pointed to what was seen as the answer. The nation had planned and managed the war. It could plan and manage the peace.

Thomas Sharp’s 1940 Pelican on Town Planning had been ‘devoured by 250,000 readers enthused by the idea that planning would not only preserve “our physical environment”, it would also “save and fulfil democracy itself.”’ When Churchill had mocked his cabinet’s enthusiasm for planning, he seemed very out of step both with the mental mood of the times but also with its suburban consequences: ‘give me the eighteenth century alley where the harlot plies her trade and none of this new-fangled planning doctrine’ he is supposed to have complained. Harold Macmillan caught the spirit of the times far more easily; ‘planning has come to stay… There is general acceptance that in so small an island one cannot allow the complete freedom which might have been possible in more primitive days.’

Development, where people should live and where they should work was no longer to be broadly set in the 1932 zoning but more minutely managed at the point of application and delivered by the state. The Town and Country Planning Act 1947 established a system with three key components:

- The nationalisation of development rights;

- The creation of a series of local Development Plans to guide development and land use (including permitting land to be safeguarded as Green Belts); and

- The submission at the point of development of all development to a discretionary planning permission process guided by these development plans as well as by more precise building standards.

The nationalisation of developments was effected by a 100 percent ‘Betterment Levy’ charged on any rise in land value consequent on private developments. In addition, the public sector was intended to play a key ‘master developer’ role. The regional plans were intended to form a key part of the national direction of the economy. This national economic direction had several spatial and planning elements including encouraging people to move to the north and preventing 1930s style ribbon development via green belts and new towns. Specifically in cities, planners intended to reduce densities, create new open spaces, segregate different zones for living or working, and improve the circulation of traffic. To their credit, 1940s planners did not hide the extent of their ambitions. One contributor to a 1944 conference on planning explained:

‘Planning means control. You have got to put people out, tell them where to live and if someone wants to build a factory, you have got to tell them ”nothing doing in Tottenham. You must build a factory in so-and-so”…Russia, Germany and Italy all had planned systems.’

In reality, the post-war state simply had insufficient resources to monopolise all development. The Betterment Levy was abolished in the 1950s. And while social housing built immediately after the Second World War was generally of a high standard (mainly cottage estates on streets with small gardens), architectural fashion and the understandable political pressure to build as many homes as possible soon started badly to undermine quality.

From the late 1960s onwards, criticism of the postwar estates and anti-urban master planning created by modernists (often but not always local government design departments) grew lounder. Modernist architects lost confidence. And from the late 1970s onwards, the state began to withdraw from leading development and design. Public sector designers retired and were not replaced. In addition, there was a profound public and professional reaction against the post-war modernist developments typified by the ‘towers in the park’ approach to design. (Although such developments are trendy again with many millennial designers they remain associated with lower property values and higher levels of deprivation than more traditional urban settlement patterns). In 1980, Circular 22/80 appears to have reduced the ability of planning authorities to turn down applications on grounds of design.

During the 1980s the role of the local plan receded with policy statements such as the 1985 ‘Lifting the Burden’ which downgraded the development plan ‘to one, but only one of the material considerations that must be taken into account in dealing with planning applications.’ This lead to a record level of successful appeals against local plan policy. This nadir in the effectiveness of the development plan produced a political backlash. Just as in the 1930s, the public kicked back against over-development. This in turn led to the Planning and Compensation Act 1991, which re-asserted the role of the local plan. This required that a local authority’s development plan be a ‘significant factor’ in what might be permitted. By the mid-1990s, the number of appeals had halved.

In short, by 1997 and after 18 years of market-based reforms, the development control system remained arguably the most significant commanding height of the economy still demonstrably within the government’s control—even if unpredictably so. However, with the concomitant withdrawal of the state from public building, pressures of under-supply of housing and development began to grow. In 1999, an influential report by the McKinsey Global Institute argued that planning constraints were one of the most important brakes on British economic growth. Although in 2005 the Government’s Planning Policy Statement 1 continued to stress the importance of the local plan, governments of all political hues have increasingly worried about the supply of new housing. The 2012 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) asserted a powerful policy presumption in favour of development. Failure to demonstrate delivery of housing can render a Local Plan out of date. Up to half of appeals against local decisions are now overturned on appeal. What can be built, and where, is arguably less clear than at any time during the last 100 years.

Conclusion

The aim of this historical survey is not to argue that we should regulate our towns and cities as if it were 1667, 1858, 1875 or 1947—the dates of, arguably, the most important statutes. That would be silly. But it is to show that the profound regulation of our towns and cities is nothing new and has been incredibly important in what we build and where. We have banned thatch, required bricks and regulated street widths for many hundreds of years. We have encouraged density, banned it and then encouraged it again. Some rules were effectively implemented. Others were not. Some permitted the growth of towns and the provision of adequate housing levels. Others have found that harder. From an historical perspective, the modern British planning system is curiously unclear and unpredictable, not just denying landowners development rights without formal consent, but also making it (in historical terms) unclear to neighbours what will be permitted. The question is not should government regulate land use and urban form but how do we do so efficiently and effectively, fairly and proportionately. The lesson must surely be that the better way to do that is to control on quality while being more liberal on the right to build, rather than the approach we currently to take which has little control on quality but is very restricting on the right to build.