Nicholas Boys Smith explains what councils, particularly rural councils with greenbelt, need to do and do fast to avoid the risk of ugly and ill-located ‘housing by appeal’

If you live in England, particularly southern rural England in the green belt, then the weeks before Christmas 2024 witnessed the most important announcement for your neighbourhood’s future for seventy years.

The Government’s new National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) is not a page turner. But ignore it at your peril. This is a loud firework not a pre-Christmas cracker. One planning King’s Counsel called its 12th December publication day, “the seminal day since the Second World War on housing delivery.” He’s probably right. There are two key reasons.

Firstly, housing targets are back in the English planning system with a vengeance. The total adds up to 370,408, over 1.8 million during this parliament or over 30,000 a month. We’ve never built more than 18,000 homes a month in the last 45 years. Make no mistake, these are big numbers. The greatest increases are in areas where there is high unmet demand for housing, mainly in the southeast. (Here’s the break down by council). Councils who don’t have a local plan in place or sufficient allocated sites for new homes will struggle to turn down speculative new applications.

Secondly, the presence of green belt will no longer be sufficient reason for councils failing to meet their housing targets. As the new NPPF puts it (at paragraph 146), when ‘an authority cannot meet its identified need for homes, commercial or other development through other means … [they] should review Green Belt boundaries in accordance with the policies in this Framework and propose alterations to meet these needs in full.’

Such a review needs to identify so-called ‘Grey Belt’ land and allocate some of it for development. The Grey Belt is defined as previously developed land and/or land which does not make a ‘strong’ contribution to three of the Green Belt’s five legally defined purposes. (The three purposes that do still count are checking unrestricted sprawl, preventing towns merging and preserving historic towns. The two purposes that do not count are safeguarding the countryside from encroachment and assisting urban regeneration.) If a site is deemed to be within the ‘Grey Belt’ then new policy is strongly in favour of development as long as there is sufficient affordable housing. It will be hard for councils not on track to meet their raised targets to say ‘no.’ And councils that do reject proposals with affordable housing included are likely to be overturned on appeal. Again, this is big news and a change since the government first consulted on planning policy back in July 2024. A senior planning lawyer has called this policy change ‘a seismic reversal of the policy test that applies to hundreds and hundreds of sites all over the country.’ He is correct.

The net effect is this: councils who don’t have a local plan in place or sufficient allocated sites for new homes will struggle to reject many speculative new applications for new homes. They will not be able to use the presence of green belt to excuse non-delivery.

If this is the ‘bad news’ (though rather good for the supply of housing which I strongly support), here is the ‘good news’. There are four critical steps that councils can and should take now to ensure that new homes and places are attractive, ‘fit in’ and do not create hectares of soulless tarmac, housing estates and boxland ‘big retail’ sprawling unsustainably and heartlessly across rural England. If they wish councils still have all the ‘hooks’ they need in the planning system to create beautiful new places not ugly ones. It is still possible to ensure that most new developments are at popular, attractive ‘gentle densities’ of about 40-60 homes per hectare rather than at 20-30 homes per hectare. Done well this is more popular, a more valuable and viable use of land and, critically for rural England, roughly halves the land take for the same number of homes whilst encouraging more neighbourly and sustainable living patterns. Here is what councils need to do.

Firstly, councils need to get their Local Plan (which allocates sites for housing and sets local policy) in place in fast as possible. Right now, only about 33 per cent of councils have Local Plans in place which are up to date and less than five years old. Councils with no Local Plan in place will be eddying leaves in the housing hurricane. Those who get their plan in place by 12th March 2025 will even get some exemptions from the raised targets. Get moving!

Secondly, councils need to put in place authority wide design-codes now. Design Codes are different from normal planning policy which tends to be verbal, fuzzy and verbose (popular with lawyers and capable of infinite disputation!) Instead, they set clear visual and numerical requirements for new developments and thus actually de-risk development by making it easier for developers, particularly SMEs, to understand local policy. They can, and should, be short, sharp and to the point. They should be empowering of new homes that are compliant. I helped persuade the last government of their utility and over the last few years an increasing number of county, district and parish councils are putting them in place, council-wide or for specific sites. When done well (many are still too verbal and fluffy), officials are finding them really helpful in saving time, discouraging really bad proposals and making it easier to ask for improvements. Critically, to work they must be firmly based in residents’ preferences for how their towns and villages should evolve. What people like is now very easy to discover thanks to online engagement techniques and visual preference surveys.

One of the great weaknesses of British planning compared to almost anywhere else is how ‘discretionary’ and high-risk British planning is with developers unclear what will or won’t be acceptable. Locally popular design codes are a way for local councils to reduce this risk and support new developments by ‘creating a clear planning ask.’ The last government was going to use the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023 to require councils to implement codes authority wide and was helping them do so. The new government still could. However, the bad news is that their response to a recent consultation (at question 5 of the NPPF consultation) half-implies that they won’t. They have also abolished the Office for Place which was starting to create national templates to make this cheap and easy for councils to achieve whilst respecting local preferences. (I think this was a mistake though – for full disclosure – I would as I was chairing it.)

The good news is that the government has not removed clear encouragement to use design codes (which was not there in national policy a few years ago). And they have even strengthened one of the tests (at paragraph 11d of the NPPF) for more sustainable and better designed new places. So, councils may not be obliged to use design policy to de-risk development. But they are not being prevented either.

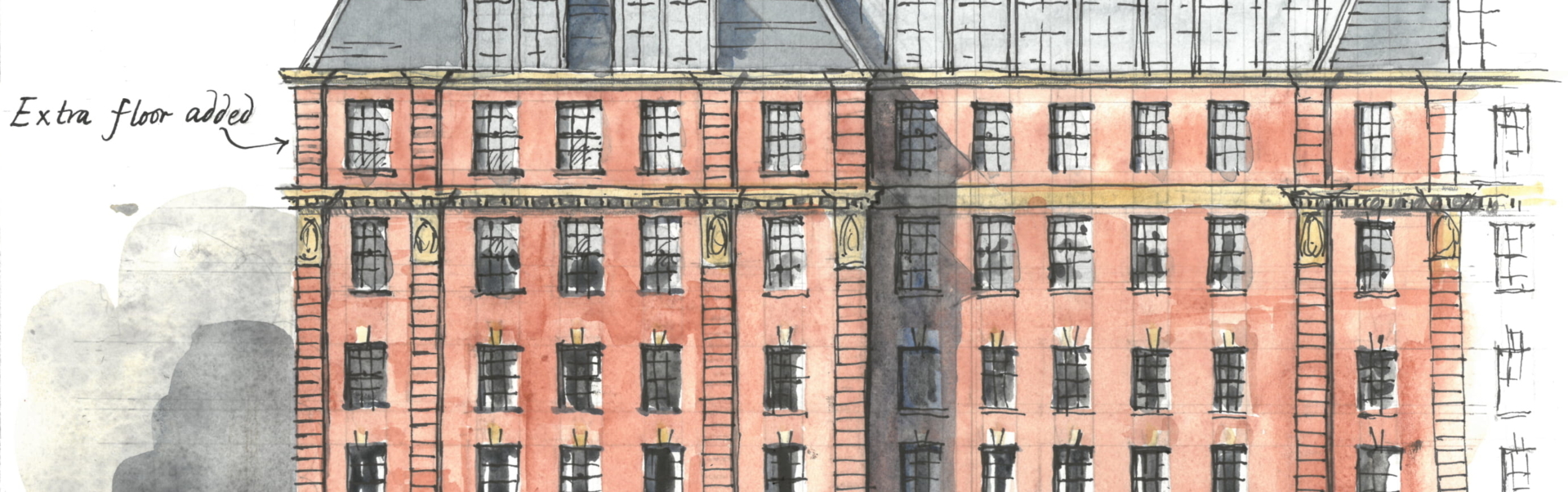

Thirdly, if councils want to reduce the pressures to build on the countryside, they can use design codes and other existing mechanism to make it easier for existing streets to intensify. This has been done brilliantly in South Tottenham. Chesham Town Council have also tried to do this in Buckinghamshire. This can really take the pressure off greenfield development by ‘turning back on’ the gentle and ongoing intensification of our urban streets that was so normal a part of life until the 1940s. Paragraph 124 of the new NPPF continues to encourage plot-by-plot intensification and new mansards. Again, the design element has been weakened in the new policy but not removed. Councils are not being obliged to use design policy to de-risk development. But they are not being prevented either. Create Streets suggested how to do this in more detail using existing statute in our 2024 manifesto.

Finally, when it comes to bigger developments councils should encourage new places which make it easy to walk and cycle about and which do not just rely on cars for all daily needs. By allowing for tighter streets and reducing the amount of land needed for parking, this is crucial for creating ‘gentle density’ new places. This can halve the required land take and takes advantage of important changes at paragraphs 115 and 116 of the NPPF (for which we argued successfully). Let me explain. Cars are great. They give the population at large immense liberty to move around the country, the countryside and the suburbs with comfort, ease and relative safety. They empower and liberate their users. However, cars diminish liberty as well as enhancing it. They are very ineffective and inefficient ways of moving around cities, towns, even historic villages and high streets. They pollute. They are dangerous to everyone else. They take up lots of space, when moving and (even worse) when parked which they are for most of the time. They undermine the productive agglomeration effects (i.e. the interplay of people and ideas that makes us richer and more productive) in towns and cities. Not for nothing are most European cities more productive than many British ones and most of our least prosperous neighbourhoods scarred by dual carriageways running through them or separating them from their nearby centre. Create Streets explored this issue in more detail in our recent report, Move Free.

By creating more places in which it is easy to get about by bike, foot or public transport as well as by car and by retrofitting existing places to be like this, we can therefore help create more homes on less land (the gift of ‘gentle density’) than by the infrastructure-heavy route we are currently taking. On the same amount of land that was used for greenfield development in 2022-23 we might have built not 112,240 homes but 220,471 homes if we had developed at an historic ‘gentle density’ of, say, 55 homes per hectare instead of 28.

Until the recent changes, developers normally had to assume that car use would continue increasing for ever. They also had to be able to demonstrate that new development would not create a new nuisance under all conceivable traffic circumstances. Implausible and extreme scenarios were thus often used to block development. This was silly. It is one of the reasons why brilliant ‘gentle density’ developments like the King’s at Poundbury or Nansledan are so rare. Policy has rightly been rewritten to focus on realistic scenarios and to make it easier for councils to require places which don’t force you into a car to get a pint of milk. Good. Here’s how to do it.

So, there you go, the government have set what Sir Humphrey would have called a ‘very courageous’ home-building target. This has immense implications for rural England particularly in the southeast and in the greenbelt.

If you run a council in rural England the time to act is right now. If you live in one, get on the phone to your councillor the moment you finish reading this article and lobby hard. Step one: get a local plan in place. Step two: set a short, locally popular, visual design code for as much of the area as possible, certainly the key sites. Step three: specifically, set an empowering code to permit attractive intensification of existing streets using existing legal mechanisms. Step four: if there are larger new developments in your area, use ‘vision-led’ transport planning not ‘predict and provide’ transport planning to benefit from the gift of ‘gentle density’ and oblige developers to be town-builders not just housebuilders.

Above all, get going. Move fast and make things. Your really don’t have a second to lose.

Addendum. Of course, I’ve only scratched the surface in this article but I hope I’ve fairly summarised hundreds of pages of policy and commentary. Importantly, I’ve not even touched on the English Devolution White Paper which pledges effectively to remove district councils and to introduce a layer of regional spatial planning. Lots to say on that but, in the short term, it makes little difference as all councils will have to respond to the NPPF even if the sword of Damocles is hanging over their organisational shoulders. Trying to hide will make it worse.

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founder and chair of Create Streets