Bristol’s former mayor and former RIBA President, George Ferguson, asks if Bristol is returning to the age of destructive planning.

Bristol’s history, special character and environment are under assault from more damaging development than we have experienced in the past 50 years, but we are in danger of sleep walking through it.

Soon after I had qualified as an architect, Times journalist Adam Fergusson published The Sack of Bath (1973), a slim but hard hitting book that has been credited with helping to save Bath from the crude planning and architecture of its time that was already eating into its history and culture. It also influenced my attitude, as I started architectural practice in Bristol, towards the importance of scale and place when building within an historic context.

The Fight for Bristol, published by Redcliffe Press with the Civic Society in 1980, features the then derelict listed buildings on Lodge Street on the cover. Without our joint intervention in the 70’s this site would have hosted another office block instead of homes for some 60 families.

Bristol is a much larger and more complex city than Bath but did, in the decades following the Second World War, suffer at the hands of highway planners and commercial developers as it strived to emulate Birmingham. Nevertheless the city to which I arrived as a student in 1965 was still steeped in its fascinating history and Bristol’s architecture was celebrated by the great architectural historian Sir John Summerson:

‘If I had to show a foreigner one English city and only one, to give him a balanced idea of English architecture, I should take him not to Oxford or Cambridge, which have developed in one special direction, nor to cathedral cities where nothing very much has happened since Henry VIII quarreled with the Pope, but to Bristol, which has developed in all directions, and where nearly everything has happened.’

Unlike Georgian Bath, Bristol is able to embrace a rich variety of architectural styles and scales, however much of its early post-war architecture, such as that around Lewins Mead, has been universally disliked and has damaged much of that wonderful legacy that Summerson refers to. More particularly it has punctured our city skyline of elegant church spires and towers with soulless bland blocks.

I had hoped that following 9/11, Grenfell and other high profile tragedies that a resurgence of environmentally and socially damaging high building development would be moderated and we would see the good sense of creating elegant streets and spaces that are the stuff of great European cities. It seems I was wrong and, while there will always be a place for the exceptional landmark, there is now a general assumption, unfortunately encouraged by our Mayor, that Bristol accepts height, almost irrespective of context.

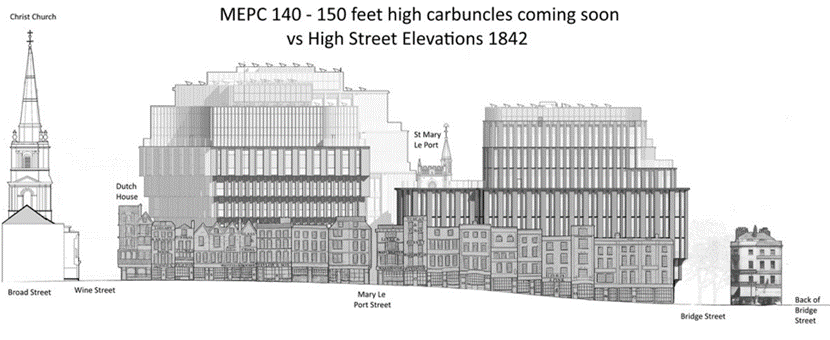

Just before Christmas we, unbelievably, saw planning permission granted for 3 vast, out of scale, office blocks at the very heart of the old city, at the West end of Castle Park, where once the medieval High Cross and iconic Dutch House stood at the crossing of Corn Street, Broad Street, Wine Street and High Street. These massive blocks, some 3 times as high as their historic neighbours, don’t contain a single home, where hundreds could have been built in a much more sympathetic form over shops and market streets. What is more they will dwarf our much more delicate historic city, that is not London or New York, and totally fail to grasp the once in a century opportunity to restore the scale, but not necessarily the style, of the High Street.

New office blocks, strongly opposed by Historic England, will dominate Castle Park and the old city. This is the architects’ illustration showing it in the best possible light but revealing the dwarfing of St Mary le Port church while the rest of the old city is concealed in all views from Castle Park.

Comparative elevations compiled by Nick Howes showing the relationship of the 3 new office blocks to the sides of the streets that were destroyed in WW2 and the relationship with the adjacent city churches that are such an essential part of the old city’s skyline and character.

The only hope is that a plea is made to the Secretary of State to save Bristol from itself as the then Secretary of State, Peter Walker, did in the case of the Avon Gorge Hotel some 50 years ago:

The irony is that our bombing of German cities led to proud citizens rebuilding their ruined historic centres, such as the city of Lübeck which became a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 1987. If one thinks of Christ Church at the top of Bristol’s High Street one can imagine a very similar scale. We may be forgiven for asking who won the war!

photo George Ferguson 2012. Lübeck’s rebuilt high street

A similar scale to Bristol’s pre-war High Street.

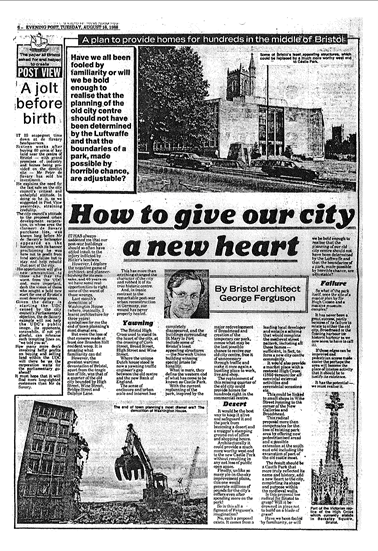

In 1988 I wrote an article in the Bristol Evening Post with a plea to give our city a new heart with streets and homes, on a European scale. Never did I imagine that we would be faced with something more akin to corporate America, which sadly seems to have become the planners’ reference. Instead we should be looking to the best of our fellow European cities such as our great twin city of Bordeaux who have sensibly kept big commercial buildings well away from their glorious historic centre which now buzzes with street life.

Photo George Ferguson

Bordeaux old city streets and buildings – spared of insensitive commercial buildings.

We have until recently had a well developed strategy of keeping large commercial buildings closer to the station at Temple Quarter, so that we could spare the centre of the city from over-scaled development. But what is shocking is that the St Mary le Port scheme, at 8 and 9 storeys, is even taller than the new office blocks in Temple Quarter, not that this was explained by planning officers.

However, maybe I should not have been surprised after the calamity at the other end of Castle Park on the site of the old Ambulance Station where a developer was encouraged to add 10 storeys to their original proposal to create a ‘landmark’ building. I cannot believe the author of the report recommending approval did so willingly. If it is a landmark it is certainly not a great one and to my mind is a dismal piece of commercial architecture that should never have seen the light of day, even at 16 storeys yet alone 26.

Bristol is now stuck with a massive concrete framed ‘tombstone’ that blights Castle Park and Old Market and pops up rudely in views from all over the city. It is no wonder that Historic England, as statutory consultees, strongly condemned both these schemes. Why were they, as the well informed guardians of our heritage, totally ignored?

Castle View – dominating Castle Park and Old Market Conservation Area

What is sinister about all this, and other proposals in and around the city, such as the scandalous commercial deal on ‘Temple Island’ for which the city may have to pick up the bill, and a huge lost opportunity to create an exemplar new community at ‘Bedminster Green’, is that unprecedented pressure is being put on planning officers to encourage high buildings against their better judgement.

That pressure must be coming, directly or indirectly, from the Mayor’s office who are clearly interfering with what is supposed to be an independent quasi-judicial process. Planning Committees are being persuaded by professional reports that fly in the face of Historic England’s advice and cannot reflect the true opinion of their professional authors who I believe to be much more discerning.

What is more, the current unquestioning alliance between business and the Mayor means there is little or no scrutiny of the commercial or environmental claims of applicants as to their schemes’ viability and sustainability – so we are left to take the word of applicants such as institutional investors Legal & General (Temple Island) and MEPC (St Mary le Port) as to the economic need for more floors. There is no such need – just greed.

Planning should always be about what is right for the place, people and environment. That is where good architecture and urbanism can play such a vital role. Unfortunately even some of the best architects are having their arms twisted by powerful clients who seem not to care about their legacy and have little understanding of Bristol.

In the Sack of Bath, Adam Fergusson quoted a beleaguered Bath citizen: “The destroyers work from nine to five every day, sitting in comfortable offices, figures and plans and projects at their finger-tips, and they get paid for what they do. The preservers have to make their own time, usually at the evenings or weekends, often finding action is too difficult or too late, and pay for legal expenses out of their own pockets.”

Bristol desperately needs a planning revolution with much greater understanding of what makes a good city, and a better world for our children, if we are not to kill the golden goose with yet more inappropriate development that has nothing to do with the creation of the more vital and fairer city and planet we should all be working towards through 2022 and beyond.

George Ferguson CBE was President of RIBA from 2003-5 and Mayor of Bristol from 2012 – 16