The architect, Robert Adam, reflects on a recent new housing planning application and why we need to ‘move the democracy forward’

I firmly believe that if we were to make more use of popular visual design codes within local plans for the ‘the type of development we like round here’ it would both make it easier for local housebuilders and help create better places. Coding is not intended just to apply to large developments but to ease all applications, give greater certainty and so encourage more SMEs to engage in development. It is believed that this will also define the parameters of design and avoid design by comment and attrition, so improving design generally. Infill or small site applications are common, numerous and typical of those promoted by SMEs, and if we multiply this by 333 local authorities in England, the aggregate impact on housing nationally is significant, putting aside the encouragement of diversity in development company size.

One residential planning application I have recently been advising highlights the problems with the current approach. In this development, we have just such an SME entering the market, very keen to promote design quality and, unusually, prepared to vigorously stand by its designers. It would be more normal and cost everyone much less in time and money – these being much the same thing – to end up with just the kind of design by comment and attrition that was proposed and, most likely, end up with a mongrel compromise design that satisfied no-one. This is notwithstanding the waste of resources and the ‘heat’ generated in these negotiations. And, indeed, the very issues that have surfaced as axiomatic in this case – height, window type and form, mass and materials – are some of the most fundamental and susceptible to simple coding.

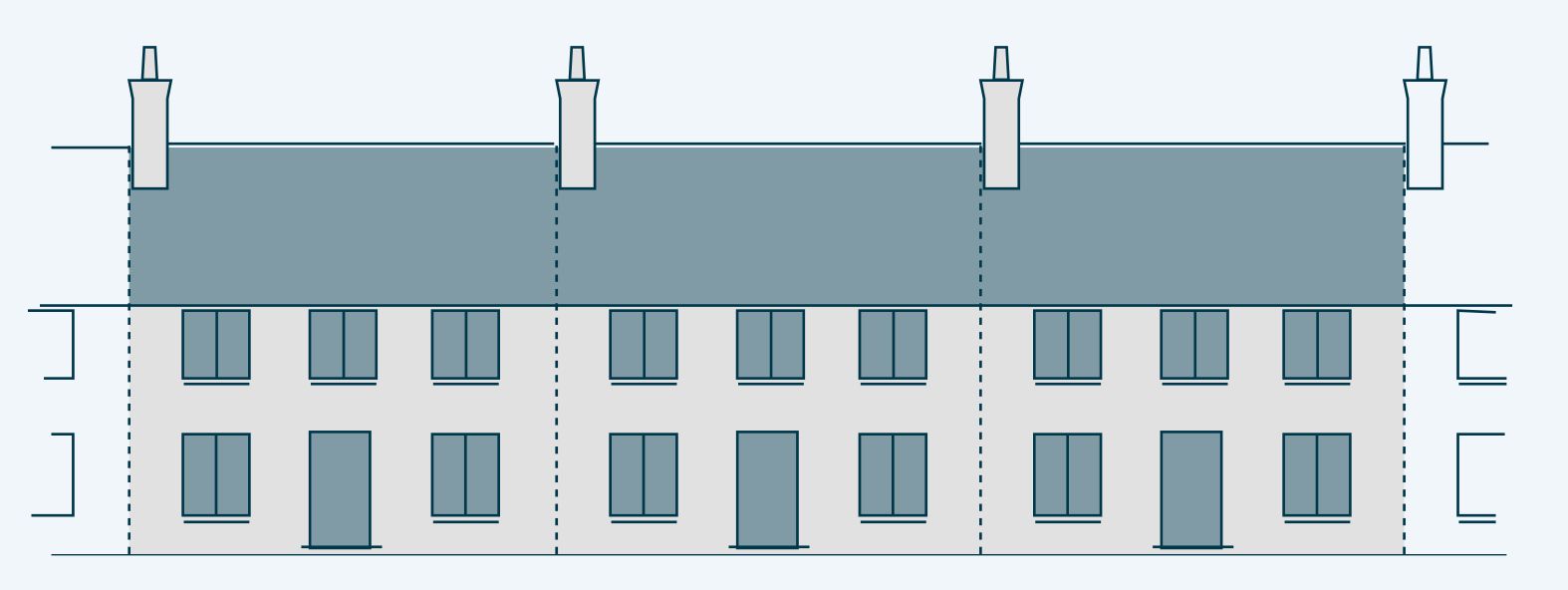

On the site in question, the principle of the development of two houses with garages at one end of a village had been established with an outline application. It is not in a conservation area and no concern was raised about the impact on a nearby and not-adjacent listed building. In the comment on this application, there were conflicting suggestions from the local authority, both concerned with style: one promoting the vernacular, the other ‘contemporary’ design.

The pre-application process took two months before the applicant took the decision to withdraw. A case officer left without any notification and after regular enquiry the applicants were informed that no new case officer was assigned and there was no programme for the paid-for meeting. On this basis, the process could easily have gone on for another month or more. The applicants decided, quite reasonably, that they could wait no longer and proceeded with the fully developed designs they had submitted for the pre-application advice. They had, however, in this process had sight of two positive statements about the designs.

Following the submission of the full application, a letter from the local authority was a shopping list of very detailed changes that amounted to a request for a complete redesign, including such minor issues as an objection to a small timber side porch and redesigning a bay window. All this and subsequent correspondence were expressed in the first person by a planning graduate – “in my view”, “from my perspective” – and it was clear that, in the time frame and from this platform, failure to agree would have resulted in a refusal. Repeated requests for meetings were ignored.

In the meantime, the parish council, which had already informed the applicant that they were going to object in principle – notwithstanding the outline consent – submitted a long and emotional objection, much of which concerned matters irrelevant in planning terms.

The case continues.

It is very clear that this typical example, that would be recognised by any architect and developer, is fundamentally flawed. Great power is put in the hands of individual officers to pursue their own design agendas and it is inefficient in time for the applicant and, indeed, the local authority. Local communities intervene so inappropriately that their intervention has to be ignored. The uncertainty and extended time process are a significant financial burden on any developer at many levels from financing to the final value that can be achieved, and has a particular impact on small firms entering the market. It also takes out any design commitment and enthusiasm and reduces design to a series of mutually unsatisfactory compromises. Effort spent in coding, in conjunction with the parish council and in the framework of the NMDC, would avoid the evident inefficiencies and conflicts that have happened in this and many other cases around the country.