Create Streets head of research Ben Southwood explains how agglomeration is the key to economic success, and why this means that more gentle density in the UK can help us

Most value in the world today is created by people working together. Natural resources like oil, or agricultural land, are still responsible for a substantial share of what we consume. But the vast majority of production is only possible with humans collaborating in complex configurations, through corporations and firms where nearly every individual employee is necessary to the quality and quantity of goods or services that are delivered.

Ultimately, the most valuable ingredient in an iPhone is not the rare trace metals it uses, but the ingenuity of the teams who came up with its various features, designed its chips and screens, and wrote its software. In general, collaboration requires co-location—physically being in the same place—to be maximally effective. The rewards to co-location are what economists call ‘agglomeration benefits’.

Recent decades have seen repeated predictions that new communication technologies—the mobile phone, the fax machine, the internet, and then Teams and Zoom—would reduce agglomeration effects by allowing people to work together remotely. Interestingly, however, this has turned out to be untrue: in fact, agglomeration effects seem to have increased. We are human animals, and despite our technological advances, physical proximity continues to matter for us. The continued value of living near others to work with them is shown by the continued buoyancy of inner city rents and house prices.

How near you need to live to others to collaborate has, however, changed enormously due to better transport. Before the train, nearly all travel within cities was at walking speed. Since building heights were capped at around six storeys by regulation, as well as by construction technology of the day, this limited the population size of cities.

Most Medieval and Renaissance cities were less than twenty minutes’ walk from one side to the other. Only the largest pre-railway cities, such as early nineteenth-century London, grew larger than this, when the economic benefits were so large that they justified the long journeys. By the 1800s, London had amassed a population of over a million. But before trams and the tube, this meant many City workers walked an hour each way from West London.

The railway, trams and underground tubes, changed this. Medieval suburbs were settlements clustered directly outside the city walls. By dramatically increasing the speed of transport, railways meant that people could for the first time live in suburbs or further towns separated from the main city by unbuilt fields. Of course, these homes did need to be clustered around the train station, since once you got off the train you were once again restricted to walking speed or an omnibus—barely faster than walking.

Later, trams, and metros like the London Underground, created contiguous suburbs as well. With stops closer together than train stations, it led to America’s famous ‘streetcar suburbs’, ‘Metroland’ around London’s tubes, and indeed suburbs across the country, ringing the major cities. The ‘effective size’ of a city—the population who could readily commute in to work at peak times—could grow dramatically.

In London’s case, this meant population growth from 1m to 7.5m in a century, creating the world’s first modern metropolis. All of these 7.5m were ‘in range’ of the others to work together. If they had been further apart, some of them would have been unable to collaborate, and they could not have captured the agglomeration benefits from working together.

The car further extended this range. Whereas transit infrastructure inherently reduces effective distance in specific directions between stops, down train, tram or bus lines, the car can range in all directions without being restricted to specific stopping points. This led to development that spread out—or sprawled—widely and at low density. Nineteenth and early twentieth century suburbs were gentle density. By mid-century this ceased to be the case. However, when roads are free at the point of use, more cars mean more congestion. Eventually the competition from cars and buses and the resulting congestion (along with many other factors) made tram networks financially unviable, and they disappeared across Britain.

Since the disappearance of trams, the decline of cycling, and the spreading out of cities, which makes walking unviable, most cities in the UK have relied heavily on single occupancy cars for nearly all of their commuting. About eighty five per cent of car commutes have no passengers other than the driver.

Relying on single occupancy car transport for commutes works only when cities have lower population density. In the mid-to-late 20th century, all of the UK’s larger cities saw very significant population declines, especially in inner city areas. This was partly due to deliberate reductions in density, and partly due to . Now that cities are roaring back into life, with growing urban populations, many more of whom can afford to own a car, so too is congestion rising.

Congestion is not just annoying; it has enormous economic costs. To collaborate with someone most effectively, you need to be able to get to the same place as them. But commutes in cities like Birmingham become extremely time-consuming during rush hour. The true economic size of a city is the number of people who are ‘within range’ of one another for collaboration. In the UK cities that rely heavily on the car, and thus face enormous congestion during rush hour, this economic size is far below their official administrative size.

The Centre for Cities, in an excellent new paper Measuring Up by Ant Breach and Guilherme Rodrigues, estimates how much damage this lack of transit options is doing to British cities, and suggests some ways to turn the situation around.

The authors compare Britain’s nine largest cities after London with similar cities on the continent. They find that British cities systematically have lower ‘effective size’ than continental cities, with far smaller fractions of Britons able to get into the centre to the best jobs than are Europeans. At peak times, our cities don’t have the agglomeration benefits they should.

The paper’s main result is extremely striking. Undoubtedly British cities outside London have seen poor investment into their transport networks. But the authors show that the bigger issue is that very few people live near the stops on the decent public transport networks they do have! On the Continent, land within walking distance of stations with convenient commutes is built up to moderate or high densities; UK train stations are often ringed by fields of rapeseed or golf courses.

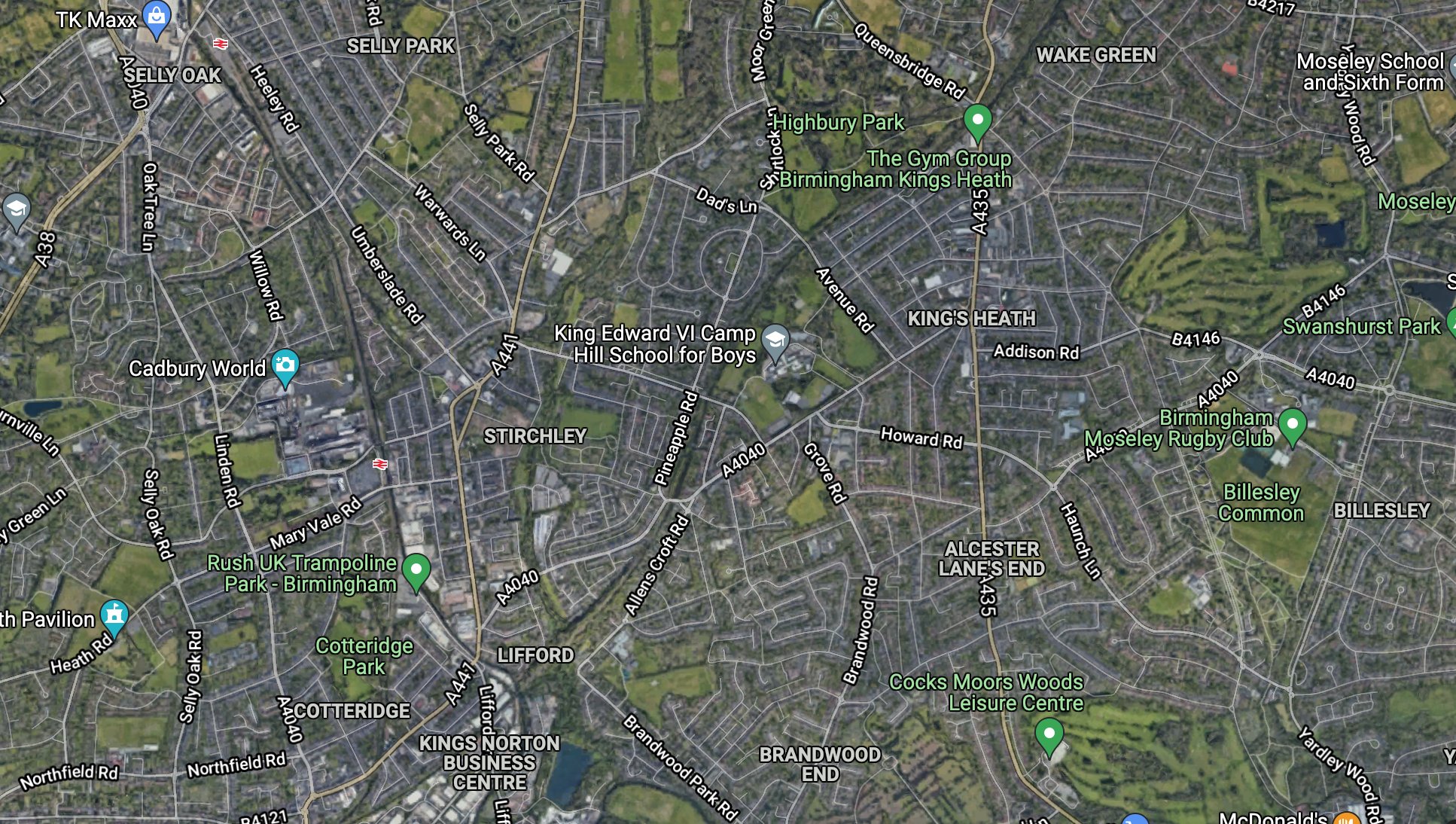

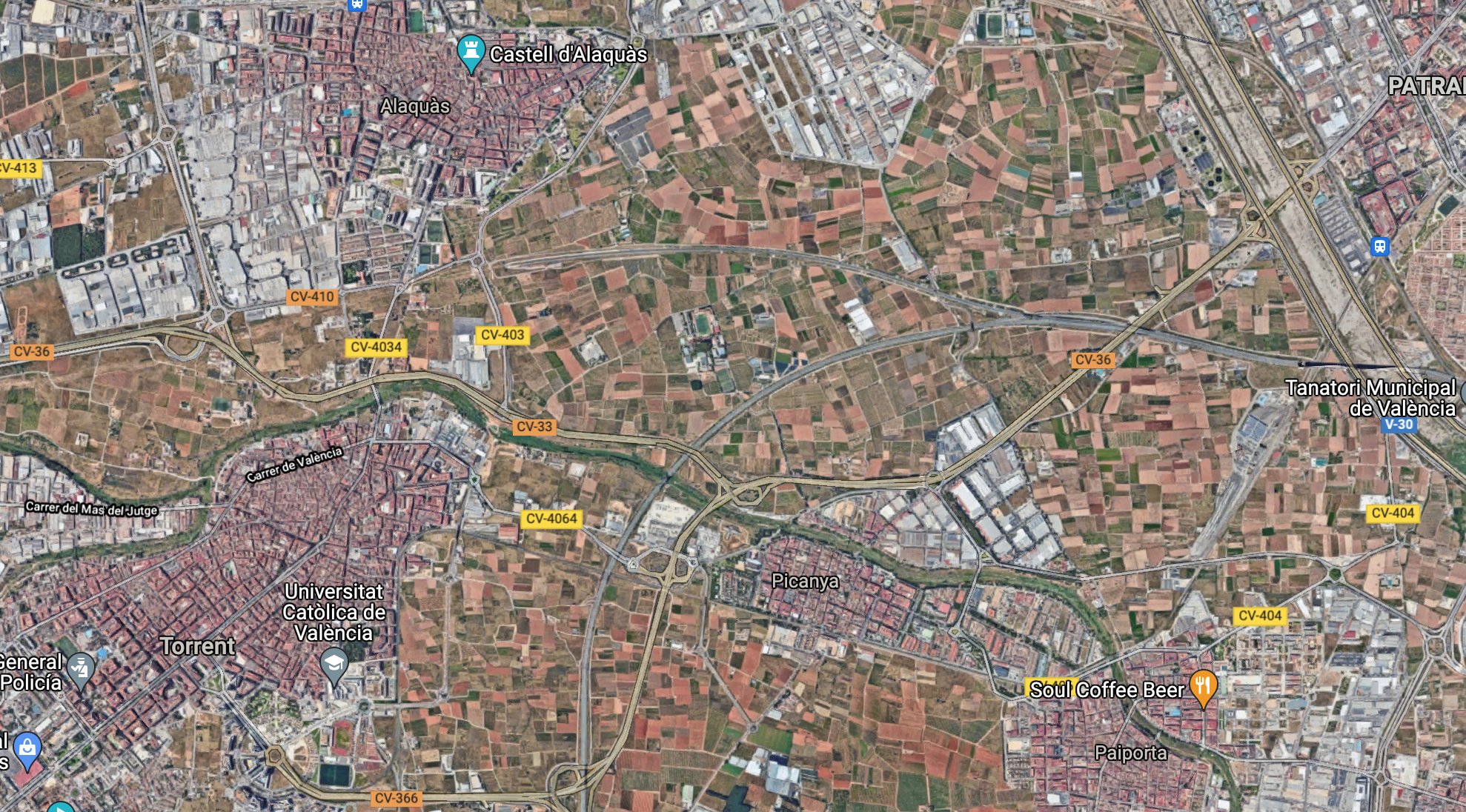

Similar distances from Valencia’s and Birmingham’s city centre, at a similar scale. Valencia’s population nearly all live within walking distance of public transport stops.

Their rough estimate implies we are forgoing agglomeration benefits worth tens of billions every year, largely due to a lack of traditional ‘gentle density’. What’s more, it is precisely the towns and cities the UK government wants to level up that are losing out most.

So what can we do? Well, one thing we can do is just to spend money on public transport. There are many shovel-ready schemes around the country with high cost benefit ratios. Some of these schemes are cheap, like painting bike and bus lanes, which raise road capacity. Others are more substantial investments, like new trams, metros and guided busways, or reopening rail lines and running extra services.

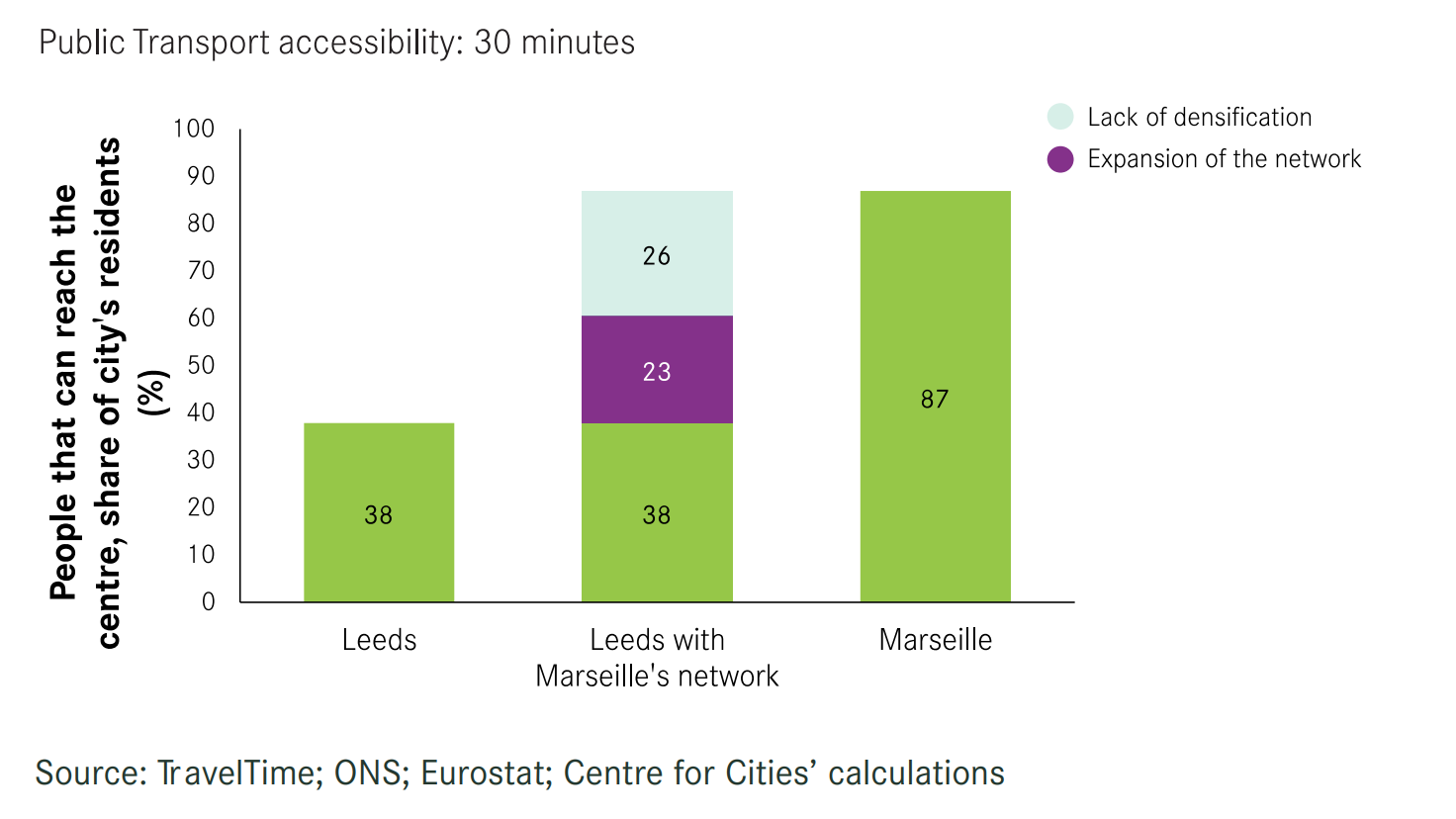

But transit is not always viable under the status quo. As we saw, British cities have responded to the existence of the car by spreading out enormously. Increasing services, or opening new stations, will have little impact if too few people live nearby to take advantage of them. In fact, Breach and Rodrigues show that even if Leeds did extend its public transport so it had the coverage of Marseille’s, its population is so much more spread out that that would not solve its transport problems. The bigger problem, for Leeds, is a lack of density clusters around existing or potential stops.

The authors suggest a range of measures to help to gently densify the areas around stations to make new and expanded transit networks more powerful. One option they suggest is the proposal for street votes, which would allow individual streets to choose to allow more density as set out in a design code they choose, if they see benefits from doing so.

They also suggest pairing new transit project funding with a requirement that local authorities use local development orders (LDOs) to give planning permission to developments around the new infrastructure. Just as infrastructure improvements make places better to live in which means more people want to move in, so also people moving in would make infrastructure improvements worth doing. This would solve the chicken-and-egg problem that infrastructure can sometimes face.

Locals already living in the area would likely look more kindly on development enabled by such LDOs than they usually would on other development—since it would come with the benefit of infrastructure as well as the inconvenience that comes with any development. Of course, the backlash against, for example, the proposed Crossrail 2 station in Chelsea shows that this may not always be a panacea.

More broadly, and this is a generational challenge, we will need to reverse the unspoken assumption that now dominates British politics—that new development will normally make places worse. Elected councillors, officials, developers, architects, planners and highways officials all need to re-learn how to create beautiful, walkable ‘gentle density’ that can provide paces to live, learn and work.

Agglomeration, collaboration, and working in productive organisations are how we create many of the important goods and services that feed, clothe, inform and entertain the nation. By improving our streets by adding more beautiful homes, we can also improve our public transport, and the resulting benefits of collaboration will bring higher standards of living across the country.

Ben Southwood is Head of Research at Create Streets